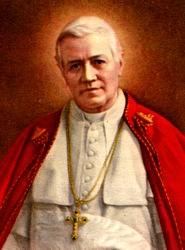

Saint Pius X

Saint Pius X

Pope

(1836-1914)

This canonized holy Pope of the twentieth century remains beloved by all as the Pope of Frequent Communion. This is indeed a beautiful and fitting title, but we would like to stress here what is less known of his pontifical works — his battle to preserve the faith against those mining it from within.

Giuseppe (Joseph) Melchiorre Sarto was born in Riese, Kingdom of Lombardy-Venetia, owned by the Austrian Empire (now Italy, province of Treviso) in 1835. He was the second born of ten children of Giovanni Battista Sarto (1792–1852) and Margarita Sanson (1813–94). He was baptized June 3rd, 1835. Giuseppe’s childhood was one of poverty, being the son of the village postman. Though poor, his parents valued education, and after finishing his elementary education, Giuseppe first received private lessons in Latin from the arch-priest of his town, Don Tito Fusaroni, after which he studied for four years at the gymnasium of Castelfranco Veneto, walking 3.75 miles (6.04 km) to school each day.

He had already announced his desire to become a priest, and his parents had approved. Their parish priest found financial aid for him. In 1850 he received the tonsure from the Bishop of Treviso, and was given a scholarship of the Diocese of Treviso in the seminary of Padua, where he finished his classical, philosophical, and theological studies with distinction. His profoundly Christian father died in 1852, His mother Margarita lived to see her son a cardinal.

On 18 September 1858, Giuseppe Sarto was ordained a priest, and for nine years was chaplain at Tombolo, having to assume most of the functions of parish priest, as the pastor was old and an invalid. He sought to perfect his knowledge of theology by assiduously studying Saint Thomas and canon law; at the same time he established a night school for adult students, and devoted himself to the ministry of preaching in other towns to which he was called. In 1867 he was named arch-priest of Salzano, a large borough of the Diocese of Treviso, where he restored the church, and expanded the hospital, the funds coming from his own begging, wealth and labor. He was consistently generous to the poor, and especially distinguished himself by his abnegation during the cholera plague that swept across northern Italy in the early 1870s. An ecclesiastic who witnessed his activity wrote that he was everywhere present. He buried the dead and confessed the sick; he saw to the needs of the various houses, he gave remedies if necessary, at all hours of the day and night. He inspired courage in all. His sisters tried in vain to moderate his zeal, but the Padre did not contract the disease, and continued to need only four hours of sleep all the time of his pastoral life.

He showed great solicitude for the religious instruction of adults. In 1875 he was made a canon of the cathedral of Treviso, and filled several offices, among them those of spiritual director and rector of the seminary, examiner of the clergy, and vicar-general; moreover, he made it possible for the students of the public schools to receive religious instruction.

In 1878, Bishop Zanelli died, leaving the Bishopric of Treviso vacant. Following Zanelli’s death, the canons of cathedral chapters (of which Monsignor Sarto was one) inherited the episcopal jurisdiction as a corporate body, and were chiefly responsible for the election of a vicar-capitular who would take over the responsibilities of Treviso until a new bishop was named. In 1879, Sarto was elected to the position, in which he served from December of that year to June 1880. After 1880, Sarto taught dogmatic theology and moral theology at the seminary in Treviso. On 10 November 1884, he was appointed bishop of Mantua by Pope Leo XIII. Upon his arrival, he asked his diocesans to come to the cathedral and to pray with him and receive Communion. As bishop, he taught catechism to the children and continued to visit the sick like a parish priest; and it seemed to them that it was his passage among them which cured them. He manifested a remarkable compassion for the working people. He defended a man who had calumniated him and who soon afterwards was ruined financially, and sent money anonymously to his wife. His chief care in his new position was for the formation of the clergy at the seminary, where, for several years, he himself taught dogmatic theology, and for another year moral theology. He wished the doctrine and method of St. Thomas to be followed, and to many of the poorer students he gave copies of the “Summa theological;” at the same time he cultivated the Gregorian Chant in company with the seminarians. The temporal administration of his see imposed great sacrifices upon him. In 1887 he held a diocesan synod. By his attendance at the confessional, he gave the example of pastoral zeal. The Catholic organization of Italy, then known as the “Opera Dei Congressi,” found in him a zealous propagandist from the time of his ministry at Salzano.

He was appointed to the honorary position of assistant at the pontifical throne on 19 June 1891.

Pope Leo XIII made him a cardinal in an open consistory on 12 June 1893. He was created and proclaimed as Cardinal-Priest of San Bernardo alle Terme. Three days after this, Cardinal Sarto became Patriarch of Venice, and never was there one more appreciated than Monsignor Sarto after his arrival. Ten years there confirmed the inhabitants’ profound affection and respect for him.

On 20 July 1903, Leo XIII died, and at the end of that month the conclave convened to elect his successor.

According to historians, the favorite was the late pope’s secretary of state, Cardinal Mariano Rampolla. However, the veto (jus exclusivae) against Rampolla’s nomination, by Polish Cardinal Jan Puzyna de Kosielsko from Kraków in the name of Emperor Franz Joseph (1848–1916) of Austria-Hungary, was proclaimed. After several ballots Giuseppe Sarto was elected on 4 August by a vote of 55 out of a possible 60 votes. His coronation took place on the following Sunday, 9 August, 1903.

At first, it is reported, Sarto declined the nomination, feeling unworthy. Additionally, he had been deeply saddened by the Austro-Hungarian veto and vowed to rescind these powers and excommunicate anyone who communicated such a veto during a conclave. With the cardinals asking him to reconsider, it is further reported, he went into solitude, and took the position after deep prayer in the Pauline chapel and the urging of his fellow cardinals.

In accepting the papacy, Sarto took as his papal name Pius X, out of respect for his recent predecessors of the same name, particularly that of Pope Pius IX (1846–78), who had fought against theological liberals and for papal supremacy.

Pius X reformed the Roman Curia with the constitution Sapienti Consilio, and specified new rules enforcing a bishop’s oversight of seminaries in the encyclical Pieni L’Animo. As the dioceses of Central and of Southern Italy were so small that their respective seminaries could not prosper, Pius X established the regional seminary which is common to the sees of a given region; and, as a consequence, many small, deficient seminaries were closed.

He also barred clergy from administering social organizations.

Interested in politics, Pope Pius encouraged Italian Catholics to become more politically involved. One of his first papal acts was to end the supposed right of governments to interfere by veto in papal elections—a practice that reduced the freedom of the 1903 conclave which had elected him.

In 1905, when France renounced its agreement with the Holy See and threatened confiscation of Church property if governmental control of Church affairs were not granted, Pius X courageously rejected the demand.

While he did not author a famous social encyclical as his predecessor had done, he opposed trade unions that were not exclusively Catholic, and denounced the ill treatment of indigenous peoples on the plantations of Peru; he sent a relief commission to Messina after an earthquake, and sheltered refugees at his own expense.

Pius X was particularly devoted to the Blessed Virgin Mary under the specific title of Our Lady of Confidence; his papal encyclical Ad diem illum expresses his desire through Mary to renew all things in Christ, which he had defined as the motto of his pontificate.

Accordingly, his greatest care always turned to the direct interests of the Church. Before all else his efforts were directed to the promotion of piety among the faithful, and he advised all (Decr. S. Congr. Concil., 20 Dec., 1905) to receive Holy Communion frequently and, if possible, daily, dispensing the sick from the obligation of fasting to the extent of enabling them to receive Holy Communion twice each month, and even more often.

Pius X’s attitude toward the Modernists was uncompromising whom he regarded as dangers to the Catholic faith. Modernism and relativism, in terms of their presence in the Church, were theological trends that tried to assimilate modern philosophers like Kant into Catholic theology, argued that beliefs of the Church have evolved throughout its history and continue to evolve. The movement was linked especially with certain Catholic French scholars such as Louis Duchesne, who questioned the belief that God acts in a direct way in the affairs of humanity, and Alfred Loisy, who denied that some parts of Scripture were literally rather than perhaps metaphorically true. In contradiction to Thomas Aquinas they argued that there was an unbridgeable gap between natural and supernatural knowledge. He saw with perfect perspicacity that the Church was falling ever more deeply into the disastrous errors of modernism, that crossroads of every heresy. Saint Pius X absolutely supported all that the great encyclicals of Popes Leo XIII and Pius IX had proclaimed or enjoined upon the authorities of the Church. He brought about the resignation of a considerable number who resisted that authority and who in ambiguous language continued to promulgate the subtle errors propagated by the manifold isms, the false doctrines of the modern world separated from Christ

The pope had at heart above all things the purity of the faith. Wherefore, in 1907, he caused the publication of the decree Lamentabili (called also the Syllabus of Pius X), in which sixty-five propositions are condemned. The greater number of these propositions concern the Holy Scripture, their inspiration, and the doctrine of Jesus and of the Apostles, while others relate to dogma, the sacraments, and the primacy of the Bishop of Rome. Soon after that, on 8 Sept., 1907, there appeared the famous encyclical Pascendi dominici gregis (or “Feeding the Lord’s Flock”), which expounds and condemns the system of Modernism. It points out the danger of Modernism in relation to philosophy, apologetics, exegesis, history, liturgy, and discipline, and shows the contradiction between that innovation and the ancient faith. Following these, Pius X ordered that all clerics take the Sacrorum antistitum, an oath against Modernism. Theologians who wished to pursue lines of inquiry in line with secularism, modernism, or relativism had to stop, or face conflict with the papacy, and possibly even excommunication.

In 1905, Pius X in his letter Acerbo Nimis mandated the existence of the Confraternity of Christian Doctrine (catechism class) in every parish in the world.

The Catechism of Saint Pius X was issued in 1908 in Italian, as Catechismo della dottrina Cristiana, Pubblicato per Ordine del Sommo Pontifice San Pio X.

The Catechism is his realisation of a simple and plain brief for uniform use throughout the whole world; it was used in the ecclesiastical province of Rome and for some years in other parts of Italy; it was not, however, prescribed for use throughout the universal church. The catechism was extolled as a method of religious teaching in his encyclical Acerbo Nimis of April 1905. An English translation runs to more than 115 pages.

Because Canon Law in the Catholic Church varied from region to region with no overall prescriptions. On 19 March 1904, Pope Pius X named a commission of cardinals to draft a universal set of laws that was to be the Code of Canon Law for most of the twentieth century. In effect the first-ever definitive Code of Canon Law was promulgated by Benedict XV on 27 May 1917, obtained the force of law on 19 May 1918 and was in effect until Advent 1983.

In 1908, the papal decree Ne Temere came into effect which addressed mixed marriages. Marriages not performed by a Roman Catholic priest were declared legal but sacramentally invalid. Priests were given discretion to refuse to perform mixed marriages or lay conditions upon them, commonly including a requirement that the children be raised Roman Catholic.

In 1908, Pius X lifted the United States out of its missionary status, in recognition of the growth of the American church. Fifteen new dioceses were created in the US during his pontificate, and he named two American cardinals. He was very popular among American Catholics, partly due to his poor background, which made him appear to them as an ordinary person who was on the papal throne. On 8 July 1914, Pope Pius X approved the request of Cardinal James Gibbons to invoke the patronage of the Immaculate Conception for the construction site of the National Shrine of the Immaculate Conception in Washington, D.C.

Saint Pius X labored until the very last days of his life. His Will and Testament contained the words: I was born poor, I have lived poor, and I wish to die poor. He died in 1914 at the age of 78 years, at the onset of the First World War, which he had foreseen. Pius X has secured great, practical, and lasting results in the interest of Catholic doctrine and discipline, and that in the face of great difficulties of all kinds. Even non-Catholics recognize his apostolic spirit, his strength of character, the precision of his decisions, and his pursuit of a clear and explicit faith.

Canonized by Pope Pius XII forty years later, on May 29, 1954, and recognized universally as a Saint for his charity, his piety, and his zeal. He will always be known as the Pope of the Eucharist.

Other than the stories of miracles performed through the pope’s intercession after his death, there are also stories of miracles performed by the pope during his lifetime. On one occasion, during a papal audience, Pius X was holding a paralyzed child who wriggled free from his arms and then ran around the room. On another occasion, a couple (who had made confession to him while he was bishop of Mantua) with a two-year-old child with meningitis wrote to the pope and Pius X then wrote back to them to hope and pray. Two days later, the child was cured. Cardinal Ernesto Ruffini (later the Archbishop of Palermo) had visited the pope after he was diagnosed with tuberculosis, and the pope had told him to go back to the seminary and that he would be fine. Cardinal Ruffini gave this story to the investigators of the pontiff’s cause for canonization.

[1.] “Pope Pius X,” 2012. [Online]. Available: http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/12137a.htm. [Accessed 31 August 2017].

[2.] “Saint Pius X – Lives of the Saints,” 24 February 2016. [Online]. Available: http://sanctoral.com/en/saints/saint_pius_x.html. [Accessed 31 August 2017].

[3.] “Saint Pius X,” Franciscan Media, [Online]. Available: https://www.franciscanmedia.org/saint-pius-x/. [Accessed 31 August 2017].

[4.] “Pope Pius X,” Wikipedia, [Online]. Available: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pope_Pius_X. [Accessed 31 August 2017].

Saint Leander

Saint Leander Saint Anthony of the Desert

Saint Anthony of the Desert Saint Eulalia

Saint Eulalia Saint Leonard of Noblac

Saint Leonard of Noblac Saint Francis Borgia

Saint Francis Borgia Saint Pius X

Saint Pius X Saint Alphonsus Liguori

Saint Alphonsus Liguori Saint Goar of Aquitaine

Saint Goar of Aquitaine Saint Ephrem the Syrian

Saint Ephrem the Syrian Saint Bede the Venerable

Saint Bede the Venerable