Blessed Marco D’aviano

Blessed Marco D’aviano

Italian Capuchin priest (1631-1699)

Feast: August 13

“So, because you are lukewarm, neither hot nor cold, I will spit you out of my mouth.” (Revelation 3:16)

A passionate servant of God, pope St. John Paul II, who conducted 104 pilgrimages all over the world during his 27year pontificate, was well aware of the dangers of being lukewarm. In His youth he witnessed the evil of Hitler’s variation of Socialism known as Fascism, then he spent many years under Communism. Both of these evil systems came into existence because of easy going lukewarm people.

On April 27 2003 he reintroduced to the world and beatified the great seventieth century warrior against lukewarm-ness, a passionate preacher who filled the confessionals, Capuchin Priest Marco D’aviano.

In the sixth century, Muhammad, a community organizer, social and political leader, founder of Islam and first Caliph (Islamic custodian, leader of the entire multi-ethnic trans-national Muslim empire), united the Arab tribes in holy war against infidels by promising them opportunities for plunder, glory and endless orgies in heaven. The number of his followers and territory occupied by them was steadily growing. The biggest obstacle to Islamic expansion was the largest and wealthiest city in Europe, Constantinople. Constantinople was instrumental in the advancement of Christianity during Roman and Byzantine times and was essential in slowing the spread of Islam by blocking the shorter passage to Europe. This is why Muslims first conquered Northern Africa which give them access to Spain. In early 711 forces led by Tariq ibn Ziyad disembarked in Gibraltar starting the westernmost expansion of both the Umayyad Caliphate and Muslim rule into Europe. For seven centuries Muslims controlled Spain but were unable to spread their dominion farther into Europe.

With the advent of the Ottoman (Turkish) Empire in 1299, the Byzantine Empire began to lose territories and Constantinople began to lose population. By the early 15th century, the Byzantine Empire was reduced just to the city and its environs, along with Morea in Greece. On 29 May 1453 after a 53-day siege lead by Sultan Mehmed II, Constantinople fell to the Ottomans.

The existence of the Ottoman Empire needed a constant holy war against Catholics to obtain a crucial source of wealth and skilled slaves.

Bulgaria and Serbia, which sit on the Balkan Mountains became the next obstacle to overcome on the way to central Europe. Almost seventy years later, in 1529 in the aftermath of the 1526 Battle of Mohács, which had resulted in the death of the King of Hungary and the descent of the kingdom into civil war, forces of the Ottoman Empire lead by Suleiman the Magnificent finally had the opportunity to capture the city of Vienna, Austria. Suleiman was facing a critical shortage of supplies, sickness, desertions, so he convened an official council on October12. It was decided to attempt one final, major assault. Extra rewards were offered to the troops.

However, this assault was also beaten back, and the defenders prevailed. Unusually heavy snowfall made conditions go from bad to worse. The Ottoman retreat turned into a disaster with much of the baggage and artillery abandoned or lost in rough conditions, as were many prisoners.

154 years later, after the conquest of the Kingdom of Hungary, the capture of the Island of Rhodes, siege of Malta, conquest of Cyprus, a 15-year war with Austria, two wars against Commonwealth of Poland and Lithuania in 1683, an Ottoman army of 150,000 accompanied by 40,000 Crimean Tatars under the command of Grand Vizier Merzifonlu Kara Mustafa Pasha reached the gates of Vienna. This began the second Ottoman siege of the city. The plan was to make Vienna the capital of a second Turkish empire in the heart of Europe. But good God did not leave His children defenseless, to punish His enemy’s pride He dispatched the Capuchin Priest Marco D’aviano.

His name was Carlo Domenico Cristofori, born in Aviano, a small community south west of Friuli in the Republic of Venice (Italy) on November 17, 1631. He was the third of eleven children of Pasquale Cristofori and Rosa Zanoni.

Confirmed in 1643, Cristofori attended high school at the Jesuit College in Gorizia. A timid, reserved, thoughtful and placid boy: difficult to predict that, on growing up, he would be a sought-for guest of all the great European courts, or that he would have to defend himself from crowds acclaiming him a saint, or that he would have become friend and counselor to Leopold I of the Hapsburgs, Emperor of the Holy Roman Empire. At 16 he ran away in his desire to assist the Venetians engaged in defending the island of Candia (Crete) under siege by the Ottoman Turks. On his way, he sought shelter at a Capuchin convent in Capodistria, where he was welcomed by the Superior who knew his family and who, after providing him with food and rest, advised him to return home. Inspired by his encounter with the Capuchins, he felt that God was calling on him to enter their Order. In 1648 aged 17 he started the novitiate at Conegliano and on taking the habit after taking religious vows in 1649 he assumed the name of Marco d’Aviano.

He completed his theological studies and on the 18th of September 1655, was ordained priest at Chioggia, dedicating himself to preaching. In 1664 he received a license to preach throughout the Republic of Venice and other Italian states. He was also given more responsibility when he was elected Superior of the convents of Belluno in 1672, and Oderzo in 1674.

His preaching, together with an exemplary life, achieved continental fame. Sermons, Lenten exercises, blessings, masses: the life of Father Marco was composed in large part of these activities. His life took an unexpected turn in 1676, when he gave his blessing to a nun, bedridden for some 13 years: she was miraculously healed. The news spread far and wide, and it was not long before the sick, and many others from all social strata, began to seek him out. A series of conversions and prodigious healings suddenly took place. The Pope, Blessed Innocent XI called him “the miracle worker of the century.”

His popularity reached France, Belgium, Holland, Switzerland, Tyrol, Bavaria, Austria, the German states, Bohemia and Slovenia which Padre Marco visited on missionary journeys requested by the bishops for the spiritual renewal of those nations. Huge crowds gathered to hear him and receive his blessing and following these gatherings extraordinary events always took place. In 1681 Innocent XI granted Father Marco the privilege, never before granted to a religious, of imparting the papal blessing, with plenary indulgence for the dead attached, on the day of general communion.

But his main priority was the practice of confession, to exhort and obtain repentance from sins, that he was most devoted to. Father Venanzio Ranier, Vice-postulator of the cause for beatification, recounts: “Father Marco was interested above all in the life of grace and the return to it of those who had strayed from it. The Apostle of forgiveness par excellence , he filled up the confessionals, so much so that the Jesuits in Belgium, where Marco d’Aviano went in 1681, wrote that they had never confessed so many as during the passage of the Italian Capuchin.

Among those who sought his help was Leopold I, Holy Roman Emperor, whose wife had been unable to conceive a male heir. From 1680 to the end of his life, Marco d’Aviano became a “guardian angel”, close confidant and adviser to him, providing the irresolute and often indecisive emperor with guidance and advice for all problems, political, economic, military or spiritual. His forceful, energetic and sometimes passionate and fiery personality proved a good complement for Leopold’s tendency to allow endless doubts and scruples to paralyze his capacity for action.

As the danger of war with the Turks grew near, in 1683 during the Ottoman army’s invasion of Europe Bl. Marco d’Aviano was appointed by Pope Innocent XI as his personal envoy to the Emperor.

As an impassioned preacher and a skillful mediator he played a crucial role in resolving disputes, restoring unity, and energizing the armies of the Holy League, which included Austria, Poland, Venice, and the Papal States under the leadership of the Polish king Jan III Sobieski.

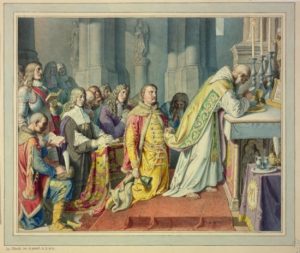

On September 11, 1683 Bl. Marco d’Aviano lead a day of prayer. At dawn on the historic day, September 12th, 1683, assisted by the Polish king Bl. Marco d’Aviano celebrated mass, during which he offered himself as a victim to the Lord for the salvation of Christendom and Europe, arousing enthusiasm and the certainty of win. A glorious victory followed the mass, victory obtained through the power of prayer, victory marking a military phase in the history of the continent and the most disastrous defeat and failure for the Ottoman’s since their foundation in 1299.

On the 25th of December 1683, a disgraced Grand Vizier Merzifonlu Kara Mustafa Pasha was executed by strangulation with a silk rope on the sultan’s orders.

Bl. Marco d’Aviano’s mission continued in the following years, promoting an alliance among European states for the liberation of the Balkans from Turkish oppression. Buda, Hungary’s capital, was liberated in 1686 after nearly one-and-a-half centuries of Turkish domination; in 1688 the stronghold of Belgrade capital of Serbia, was also liberated. He always maintained a strictly religious spirit, to which any violence and cruelty were repugnant. At the siege of Belgrade Padre Marco obtained the sparing of 800 Turkish soldiers’ lives.

In the meantime, he continued to devote himself to preaching in a fiery and persuasive manner, especially in the Veneto area. His Lenten sermons remain famous. He maintained epistolary contact with influential people of the day, especially as spiritual adviser to emperor Leopold I.

At 11 pm on 13 August 1699 during his last journey to Austria’s capital, worn out by his strenuous life, gripping the crucifix he had always carried with him, in the presence of the emperor and his wife Eleonora, Bl. Marco d’Aviano died. He was buried in the Capuchins’ church in Vienna.

References and Excerpts

[1] “30Giorni | The preacher who filled the confessionals (by Gianni Cardinale).” http://www.30giorni.it/articoli_id_787_l3.htm (accessed Aug. 28, 2020).

[2] “ENGLISH | Beato Marco d’Aviano.” https://www.beatomarcodaviano.it/english/ (accessed Aug. 28, 2020).

[3] “Marco d’Aviano,” Wikipedia. Mar. 15, 2020, Accessed: Aug. 28, 2020. [Online]. Available: https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Marco_d%27Aviano&oldid=945749489.

Saint Victor of Marseille

Saint Victor of Marseille Saint Irenaeus

Saint Irenaeus Saint Mammertus

Saint Mammertus Saint Leo the Great

Saint Leo the Great Saint Wulfran

Saint Wulfran Saint John of Matha

Saint John of Matha Saint Hilary of Poitiers

Saint Hilary of Poitiers Saint Thomas Becket

Saint Thomas Becket Saint Andrew Avellino

Saint Andrew Avellino