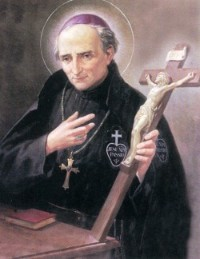

Saint Vincent Strambi

Saint Vincent Strambi

Passionist Priest, Bishop of Macerata and Tolentino (1745-1824)

Feast – September 25

In tough times, times of war and persecution, God gives his children holy people, prophets in the Old Testament days and saints in our modern times, using them to restore faith, give hope and grant victories to those who put their trust in Him. One of these saints is St. Vincent Strambi.

In 1689, St. Margaret Mary Alacoque, the Visitation Order nun and mystic, received a private request from Jesus to urge the King of France, Louis XIV, to consecrate the nation to the Sacred Heart, so that He may be “triumphant over all the enemies of Holy Church.” Louis XIV, along with his successors, refused to consecrate the nation.

In May 1789, 100 years after St. Alcoque’s vision, King Louis XVI wanted to raise taxes to fill the hole in his budget, so he called the convocation of the Estates General-the general assembly representing the French estates of the realm: the clergy, the nobility, and the commoners. With the idea of Taxing the Rich, Louis XVI acceded to popular demand that the Commons be allocated twice as many delegates as each of the other two Estates. In the elections of early spring 1789, the First Estate was allocated 303 delegates, the Second Estate 282, and the Third Estate 578. A majority of the Third Estate were ambitious local leaders, community organizers and lawyers seeking a quick elevation in ranks. On June third the Estate formed the National Assembly and invited the other two estates to join, many of which opposed the monarchy and high taxes. This shifted the balance in the assembly.

Continuing unrest, political conflict and economic distress culminated in the Storming of the Bastille on the 14th of July, which led to a series of radical measures by the Assembly, including the abolition of feudalism and imposition of state control over the Catholic Church in France. The next three years were dominated by the fight for political control between the Girondists, a loosely knit political faction of classical liberals mostly active in the Legislative Assembly campaigning for the end of the monarchy, and the Montagnards, a group of the most radical members of the highest benches in the National Convention.

On the 27th of August, 1791, Frederick William II of Prussia and the Habsburg Holy Roman Emperor Leopold II declared joint support for King Louis XVI of France. Eight months later, following a vote of the revolutionary-led Legislative Assembly, France declared war on Austria. Prussia, having allied with Austria in February, declared war on France in June 1792 and in July an army of Prussians joined the Austrian side and invaded France. The capture of Verdun by Prussians on 2 September 1792 triggered the September massacres in Paris. On the same day, around 1:00 pm, Georges Danton (French Minister of Justice) delivered a speech in the assembly, stating: “We ask that anyone refusing to give personal service or to furnish arms shall be punished with death”. Within the first 20 hours more than 1,000 prisoners (enemies of the revolution) were killed, among them women, children and over 170 Catholic priests. On the 20th of September, France counterattacked with victory at Valmy and two days later the Legislative Assembly proclaimed the French Republic. In January 1793 king Louis XVI was executed.

In May Jean-Paul Marat, one of the leading figures in the September massacres, with the support of the Paris commune (government of Paris) demanded that the Girondin representatives in the National Convention, who in January had voted against the execution of the king, must be brought before the Revolutionary Tribunal. A mob of thousands of armed citizens surrounded the Convention and forced the deputies to deliver the 29 representatives and two Ministers denounced by the Commune. The Montagnards took control over Convention and created the Committee of Public Safety, headed by Maximilien Robespierre. The Reign of Terror to eradicate alleged “counter-revolutionaries” started. By the time it ended in July 1794, at least 300,000 suspects were arrested, and over 16,600 had been executed throughout France of which 2,639 were in Paris alone. An additional 40,000 may have been summarily executed or died awaiting trial. As the Terror accelerated, members of Convention felt more and more threatened. In his speech on the 26th of July, 1794, Robespierre spoke of the existence of internal enemies, conspirators, and calumniators within the Convention and the governing Committees. The next day Robespierre (useful idiot) was arrested with 90 of his closest comrades and executed by guillotine on the 28th of July, 1794. The reign of the Committee of Public Safety was ended, but the exceptional revolutionary measures continued. The period of the less intensive “White Terror” followed. In July 1794, the Convention established a committee to draft the Constitution, which was presented to the Convention and formally adopted on 22 August, 1795.

The new Constitution was officially proclaimed on the 23rd of September, 1795, but the new Councils had not yet been elected, and the Directors had not yet been chosen. The leaders of the royalists and constitutional monarchists chose this moment to try to seize power.

The members of the Convention were aware that the planning was underway and created a group of five deputies, led by Paul Barras, as an unofficial directory to deal with rebellion.

On the 5th of October, 1795, the armed royalist insurgents march in two columns along both the right bank and left bank of the Seine toward the Tuileries. They were confronted by the artillery of sous-lieutenant Joachim Murat at the Sablons and by Napoleon Bonaparte’s soldiers and artillery in front of the church of Saint-Roch. Over the next two hours, Bonaparte’s cannons and the gunfire of his soldiers brutally killed some four hundred insurgents and ended the rebellion. Bonaparte was promoted to General of Division and General in Chief of the Army of the Interior. Shortly after, in November 1795 the French Directory was created and took power. After six years of revolutionary government ruling, France faced a shortage of food and necessities. Strict distribution, price control and inflation lead to a situation when the fixed prices could not cover the cost of production, and supplies dropped even more. In this situation, conquering neighboring regions that had not been ruined by revolution and robbing them was a quick fix. A series of military victories, many won by Napoleon Bonaparte who demanded gold or silver from each city he conquered, threatening to destroy the cities if they did not pay, made him a national hero. In November 1799, the Directory was replaced by the Consulate with Bonaparte as First Consul and in 1804 Napoleon I was declared the Emperor of the French. In 1808 Napoleon Bonaparte used the French alliance with Spain to force King Ferdinand VII to abdicate, giving the throne to Bonaparte’s brother Joseph. This started large-scale guerrilla style war that lasted six years. The result was that France lost an ally and control over the Iberian Peninsula.

In the summer of 1812 Napoleon launched an invasion of Russia. The Russians unable to stop the advancing 600,000 men, including foreign recruits, of Bonaparte’s Grande Armée employed a scorched-earth military strategy that aimed to destroy anything that might be useful to the enemy. the Grande Armée reached Moscow on the 14th of September, 1812, but was ultimately forced to march back westward. Due to constant harassment by Russian partisans, the frigid cold, starvation, and diseases, the army of 600,000 dwindled to only 120,000 who survived to leave Russia. After defeating Napoleon in the Battle of Leipzig in October 1813, the army of the Sixth Coalition against France invaded France and captured Paris in late March 1814. Under the Treaty of Paris, signed on the 30th of May, 1814, Napoleon was exiled to the island of Elba. However, on the 26th of February, 1815, Napoleon escaped from Elba in the French brig the Inconstant and two days later, landed at Golfe-Juan with 607 Grenadiers of the Old Guard, 118 Polish Lancers, 300 Corsicans, 50 Elite Gendarmes, and 80 civilians, he reached Paris on the 20th of March. By June, his armed forces numbered 200,000. The Allies responded by forming a Seventh Coalition. A number of battles were fought leading to Napoleon’s final defeat at Waterloo.

Upon Napoleons’ return to France his brother-in-law, Joachim-Napoleon Murat, King of Naples quickly raised a 50,000-man army and declared war on Austria on March 15th.

Advancing north, he won a series of victories over the Austrians but, once defeated on April 8th or 9th at Occhiobello was forced to fall back. Retreating, he ended the siege of Ferrara and reconcentrated his forces at Ancona. Pursued by Austrian forces, Murat set up his headquarters at Macerata, near Tolentino, planning to use that location for battle.

The people, out of fear for their lives and the certain devastation facing Macerata, turned to their Bishop for guidance. His response was to gather priests and seminarians in his private chapel to beg for God’s intercession and after one and a half hours he rose and declared that Macerata would be saved through the intercession of the Mother of God. He met with the King of Naples and begged him not to enter the town, to which Murat agreed. Then he secured the assurances of the Austrian generals that Murat’s soldiers would not be slaughtered.

The Battle started on 2 May 1815 near Tolentino. After two days of fight, the Austrian army had 11,938 men 1,452 horses and 28 artillery pieces after losing 700 killed 100 wounded, but had successfully routed Murat’s forces, which numbered, 25,588 men, 4,790 horses 58 artillery pieces and had suffered 1,120 killed, 600 wounded and 2,400 captured.

The Holy Bishop who saved Macerata and Tolentino and lives of many soldiers and civilians is St. Vincent Strambi.

St. Vincent Strambi was born in 1745 in Civitavecchia, Italy, as the last of four children to a pharmacist, Giuseppe Strambi, known for his charitable works, and Eleonora Gori, noted for her piety. His three elder siblings all died in childhood. He was a troublesome child who liked to play practical jokes on his friends, but at the same time his good nature inspired him to give away his own overcoat or shoes to any homeless child he encountered. The Friars Minor oversaw his education. In his teenage years he started to teach his younger fellow students the catechism. It was at this time that he became quite attracted to the notion of the religious life. His parents seeing his religious fervor encouraged him to become diocesan priest. At age 15 he entered the seminary at nearby Montefiascone and in 1762 received clerical “tonsure.” Noted for his oratorical gifts, he was sent to Rome for studies in Sacred Eloquence and then continued his theological studies with the Dominicans at Viterbo. After his ordination as a deacon in 1767, he made a retreat amid the Passionists of Monte Fogliano, led by St. Paul of the Cross, founder of the order. In the Passionist house he found his vocation and decided to enter that religious community instead. He asked the founder to be admitted into the order, but he was refused. Ordained to the priesthood on the 19th of December, 1767, he returned to Rome to further his theological studies. The life of contemplation, essential for any fruitful works, was his desire.

He still felt called to the Passionists and made several trips to see St. Paul of the Cross. In September 1768 the founder relented, and St. Vincent began his novitiate. He made his profession on the 24th of September, 1769. St. Vincent had just six years to absorb the spirit of the congregation from St. Paul of the Cross. He was sent to Vetralla for two further years of studies with a particular emphasis on the Church Fathers, on Sacred Scripture and sermon writing.

His studies of religion continued throughout his lifetime; he knew by heart Sacred Scripture and all the works of Saint Thomas Aquinas. As he studied, he seemed to see around his desk the faces of his spiritual children, waiting for the bread of life he was destined to break for them. This method of thinking about and praying for your future spiritual children before they study has been preserved among his followers in the Order. His preaching was so simple that all could easily understand. He never used notes but lectured according to the needs of his listeners. When he preached missions – a focal point of the Passionist charism – he drew large crowds. On several occasions he preached before Bishops and Cardinals.

In 1773 he was made a professor of theological studies in charge of the training of young students who were selected for future missionary preaching at the newly acquired order’s house in Rome, at Santi Giovanni e Paolo. Here he would eventually write a manual on Sacred Eloquence, and it was here that in October 1775 he was present at the death of St. Paul of the Cross. The founder said to St. Vincent on his deathbed: “You will do great things! You will do great good! I recommend to you this poor Congregation!”

In 1780 he became rector of the Community of Saints John and Paul. In 1781 he was elected provincial, serving as provincial and general consultor at the same time, preaching missions as often as possible. St. Vincent published a biography on St. Paul of the Cross, and the testimonies of eyewitnesses used in the biography were also used during the canonization process. It is said that he wrote the life of St Paul of the Cross on his knees, out of reverence for the founder.

On the 29th of August, 1799, Pope Pius VI died. In 1801 the new Pope Pius VII appointed St. Vincent as the Bishop of Macerata-Tolentino, becoming the first bishop to come from the Passionists. He rushed to Rome in an effort to get the appointment cancelled before it become official. He took his case to the pope who listened and told St. Vincent that the decision to name him bishop was “a divine inspiration” and is final. His friend Cardinal Antonelli presided over his episcopal consecration at Santi Giovanni e Paolo.

Loyal to the pope and Holy See as bishop of Macerata and Tolentino he was a true pastor of souls, full of zeal and discipline. St. Vincent Strambi in heart was always Passionist, in private he would wear the Passionist habit. As a man of prayer he regretted being unable to dedicate more than five hours to prayer each day, and as a community observance he took great care in the education and ongoing formation of diocesan priests, paying close attention to the teaching standards in the diocesan seminaries. He visited every religious house of his diocese, then the Canons and the parish priests. He preached for his clergy a beautiful mission, then organized specialized services for the various professions of the laity. He reduced his diocesan expenditures to a minimum, to be able to give more to the poor. He was especially attentive to the people in his care during a typhoid epidemic and when a famine struck the city. He called in the poor and gave them alms; he visited the hospitals and the prisoners, blessed, embraced and helped them, established orphanages and homes for the aged. Occasionally he was seen begging on poor’s behalf.

The Napoleonic invasion of the Papal States and the anti-religious decrees forced St. Vincent to flee Rome in 1798, but he managed to return to Rome shortly thereafter. In March 1808, the puppet of France, the Kingdom of Italy invaded the papal provinces Ancona, Macerata, Fermo, and Urbino and by Napoleonic decree the annexed provinces became part of the French empire. The French ordered that this decree be read in all churches, but St. Vincent refused to do so. He also refused to provide the French with a list of all the men in his diocese who would be suitable for service in the armed forces. The French arrested him in September 1808 for refusing to take the oath of allegiance to the French invaders and was then exiled and cut off from his diocese. He was first sent to Novara, then in October 1809 to Milan. From there he continued to guide his people through correspondence. He returned to his see in 1814 with vast crowds lining the route of his return.

Six years of French occupation had a negative influence on the infrastructure, and morality of the residents. St. Vincent instituted strict reforms to end corruption, which were met with resistance to the point that he received death threats, but after St. Vincent single-handedly saved Macerata and Tolentino from devastation a year later, the opposition vanished. Pope Pius VII on 10 March 1823 made him Cardinal.

He wished to resign as bishop at the age of seventy-eight, and Pope Leo XII ceded to his wish, but asked him to come to Rome as his counselor. That his life was soon to end was revealed to him, and when the Holy Father was about to die that same year, he offered his life to save that of the Vicar of Christ. He did not say so directly, but told everyone not to be anxious, because the Pope would live. Someone he knew had offered his life for him, he added. The prayer was answered on the very day he said this, December 24th; the Pope rose, suddenly cured. Three days later St. Vincent was struck by apoplexy and died on January 1st, 1824.

Pope Pius XI beatified him in 1925 and St. Vincent Strambi was canonized on 11 June 1950 by Pope Pius XII.

References and Excerpts:

[1] “Napoleon,” Wikipedia. Sep. 05, 2022. Accessed: Sep. 05, 2022. [Online]. Available: https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Napoleon&oldid=1108706226

[2] “French Revolution,” Wikipedia. Aug. 26, 2022. Accessed: Sep. 05, 2022. [Online]. Available: https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=French_Revolution&oldid=1106806819

[3] “Battle of Tolentino,” Wikipedia. Aug. 08, 2022. Accessed: Sep. 05, 2022. [Online]. Available: https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Battle_of_Tolentino&oldid=1103041691

[4] “Saint Vincent Strambi, Passionist Priest, Bishop of Macerata and Tolentino.” https://sanctoral.com/en/saints/saint_vincent_strambi.html (accessed Sep. 05, 2022).

[5] “St Vincent Strambi | Passionists Ireland and Scotland.” https://passionists.ie/st-vincent-strambi/ (accessed Sep. 05, 2022).

[6] “Vincent Strambi,” Wikipedia. Mar. 07, 2022. Accessed: Sep. 05, 2022. [Online]. Available: https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Vincent_Strambi&oldid=1075762366

Saint Philip Benizi

Saint Philip Benizi

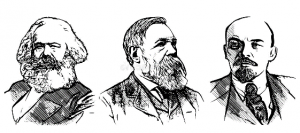

upper middle-class income and the owner of several of vineyards along the Moselle River. Friedrich Engels (1820- 1895) was born into the wealthy Engels family, owners of large cotton-textile mills in the expanding industrial metropoles of Barmen and Salford. These two German philosophers, political theorists, social scientists and journalists saw that the French Revolution of 1789 had elevated an artillery officer, Napoleon Bonaparte, to the position of General at age 24, and later to “Emperor of France.” In their ambition, they viewed this as an opportunity to rise to power through a revolution, but on a global scale.

upper middle-class income and the owner of several of vineyards along the Moselle River. Friedrich Engels (1820- 1895) was born into the wealthy Engels family, owners of large cotton-textile mills in the expanding industrial metropoles of Barmen and Salford. These two German philosophers, political theorists, social scientists and journalists saw that the French Revolution of 1789 had elevated an artillery officer, Napoleon Bonaparte, to the position of General at age 24, and later to “Emperor of France.” In their ambition, they viewed this as an opportunity to rise to power through a revolution, but on a global scale. After adopting the new constitution in 1999, Chávez focused on enacting social reforms as part of the Bolivarian Revolution. He implemented three main policies which are the pillars of socialism: Widespread nationalization of private industry; currency and price controls; and the fiscally irresponsible expansion of welfare programs. These policies destroyed production and crushed foreign investments, creating shortages of basic necessities.

After adopting the new constitution in 1999, Chávez focused on enacting social reforms as part of the Bolivarian Revolution. He implemented three main policies which are the pillars of socialism: Widespread nationalization of private industry; currency and price controls; and the fiscally irresponsible expansion of welfare programs. These policies destroyed production and crushed foreign investments, creating shortages of basic necessities. In the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington, D.C. we can find the famous poem “First they came…” of Lutheran pastor Martin Niemöller, who was arrested in 1939, sent to the Sachsenhausen-Oranienburg concentration camp, then later to Dachau before being freed in 1945 by the Allies.

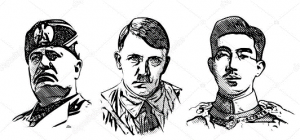

In the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington, D.C. we can find the famous poem “First they came…” of Lutheran pastor Martin Niemöller, who was arrested in 1939, sent to the Sachsenhausen-Oranienburg concentration camp, then later to Dachau before being freed in 1945 by the Allies. Reich, Hitlers party grow so rapidly that in 1923, he attempted to seize power. He enlisted the help of World War I General Erich Ludendorff for an attempted coup known as the “Beer Hall Putsch” to overthrow the Bavarian government. Arrested on 11 November 1923 for high treason he was sentenced to five years’ imprisonment and released a year later he gained national recognition. He was seen by patriots as one who could restore the greatness of Germany. The communists, socialists, and the trade unionists, of Communist International (Comintern) viewed him as one who could help start a communist revolution in the country. To industrialists and businessmen, many of them Jewish, Hitler was a potential source of new, big, lucrative government contracts. To the impoverished, he was the one who would take care of their basic needs. Over the next eight years the Nazi Party grew nationally to the point that in 1932 it caused a parliamentary impasse. On 30 January, 1933, President Paul von Hindenburg, to break the parliamentary gridlock, appointed Hitler as chancellor which shifted the balance to the benefit of the Nazi party. To secure his party’s gains, Hitler had to eliminate the communist party. It was not a sentimental move, but a tactical one. The communist parties had secret military wings in every country with the purpose to prepare for the civil war. In Germany it was the M-Apparat of the Communist Party (Roterfrontkämpferbund) which with the help of Soviet Russia and Comunist International could initiate a successfull revolution in Germany which had been demilitarized after WWI.

Reich, Hitlers party grow so rapidly that in 1923, he attempted to seize power. He enlisted the help of World War I General Erich Ludendorff for an attempted coup known as the “Beer Hall Putsch” to overthrow the Bavarian government. Arrested on 11 November 1923 for high treason he was sentenced to five years’ imprisonment and released a year later he gained national recognition. He was seen by patriots as one who could restore the greatness of Germany. The communists, socialists, and the trade unionists, of Communist International (Comintern) viewed him as one who could help start a communist revolution in the country. To industrialists and businessmen, many of them Jewish, Hitler was a potential source of new, big, lucrative government contracts. To the impoverished, he was the one who would take care of their basic needs. Over the next eight years the Nazi Party grew nationally to the point that in 1932 it caused a parliamentary impasse. On 30 January, 1933, President Paul von Hindenburg, to break the parliamentary gridlock, appointed Hitler as chancellor which shifted the balance to the benefit of the Nazi party. To secure his party’s gains, Hitler had to eliminate the communist party. It was not a sentimental move, but a tactical one. The communist parties had secret military wings in every country with the purpose to prepare for the civil war. In Germany it was the M-Apparat of the Communist Party (Roterfrontkämpferbund) which with the help of Soviet Russia and Comunist International could initiate a successfull revolution in Germany which had been demilitarized after WWI. However, Hitler had no problem working together with the communists if this benefited him and his agenda. Just before starting WWII in August 1939, Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union signed the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact beginning almost two-year period of military and economic cooperation between two countries starting with the invasion of Poland. Germany invaded Poland on September 1, 1939, from west and the Soviets joined them seventeen days later attacking from east.

However, Hitler had no problem working together with the communists if this benefited him and his agenda. Just before starting WWII in August 1939, Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union signed the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact beginning almost two-year period of military and economic cooperation between two countries starting with the invasion of Poland. Germany invaded Poland on September 1, 1939, from west and the Soviets joined them seventeen days later attacking from east. Hitler needed a target for the people to hate. The Jews, many of whom were successful, prosperous, highly educated and visibly different; different culture, different language, religion and race, already envied by many Germans, were the obvious choice. Around 6 million Jews died in concentration camps, Slavs were another lesser people to be despised and for elimination. Just from Poland during WW II 1.5 million were deported to German territory for forced labor and 1.9 million non-Jewish civilians killed in concentration camps. All of that to gain power, more power, the absolute power, which “corrupts absolutely” (Sir John Dalberg-Acton).

Hitler needed a target for the people to hate. The Jews, many of whom were successful, prosperous, highly educated and visibly different; different culture, different language, religion and race, already envied by many Germans, were the obvious choice. Around 6 million Jews died in concentration camps, Slavs were another lesser people to be despised and for elimination. Just from Poland during WW II 1.5 million were deported to German territory for forced labor and 1.9 million non-Jewish civilians killed in concentration camps. All of that to gain power, more power, the absolute power, which “corrupts absolutely” (Sir John Dalberg-Acton). Saint Eugenius

Saint Eugenius Saint Prosper of Aquitaine

Saint Prosper of Aquitaine Saint Gregory Nazianzen

Saint Gregory Nazianzen Saint Anselm

Saint Anselm Saint Thomas Aquinas

Saint Thomas Aquinas Saint Benedict of Anian

Saint Benedict of Anian