Saint Fidelis of Sigmaringen

Saint Fidelis of Sigmaringen

Martyr (1577-1622)

Feast- April 24

To restore the moral integrity of the clergy and end the investiture of bishops by lay rulers, the Church enacted the Gregorian Reforms of the late 11th century. These reforms reduced the Church’s dependence on local rulers, making it a powerful player in world affairs.

At the time, books were hand copied by monks, which meant they were expensive and primarily accessible to churches and monasteries. This enabled the Catholic Church to guard against accidental or intentional misinterpretation while also educating society. This situation changed after 1440, when the German goldsmith Johannes Gutenberg invented the movable-type printing press. Soon thereafter, the printing press was used to publish books and documents besides the bible and salvation-oriented literature. Soon after Martin Luther nailed his Ninety-five Thesis to the door of All Saints’ Church in Wittenberg on 31 October 1517, his wealthy friends had it translated from Latin into German, printed and spread across the Holy Roman Empire. By 1519, Luther’s teachings had spreading across France, England and Italy. Many local rulers and nobility, seeking freedom to pursue unholy desires without risking condemnation by the Church, and consequently their subjects, happily sponsored Luther’s “reformation.”

After refusing to renounce all his writings at the demand of Pope Leo X, Martin Luther was excommunicated on the 3rd of January, 1521. The Edict of Worms (a formal deliberative assembly of the Holy Roman Empire called by Emperor Charles V on the 25th of May, 1521), declared Luther an outlaw, banned his literature, and required his arrest. However, under the protection of the powerful Frederick III, Elector of Saxony, Luther was free to attack the Catholic Church, undermine its teachings and authority while promoting obedience to the local overlords.

While Martin Luther led the Protestant Revolution in modern day Germany, Ulrich Zwingli led the revolt in Switzerland, John Calvin in France, John Knox in Scotland, Thomas Cranmer (under Henry VIII) in England, and many others. This led to violent riots and wars, and savage atrocities were committed in the name of reformation. In response to the Protestant Reformation, the Council of Trent began the Catholic Counter-Reformation in 1545. This council was a comprehensive effort composed of apologetic, polemic documents, and ecclesiastical configuration. This effort included codification of the uniform Roman Rite Mass; foundation of seminaries for the proper training of priests in the spiritual life and the theological traditions of the Church; and public defense of the sacraments and pious practices, which were under attack by the Protestant reformers. Jesuits under St. Ignatius of Loyola and many faithful from other religious orders undertook the educational and missionary work to bring back the lost sheep to the faith.

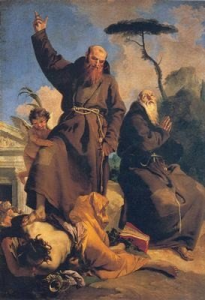

Capuchin, St. Fidelis of Sigmaringen is one of those who answered the call and like Our Lord Jesus sacrificed his life to save others.

Mark Rey was born in 1577 to noble parents in the Swabian (southern Germany) town of Sigmaringen, the Principality of Hohenzollern-Sigmaringen, where his father Johann Rey was burgomaster (mayor). His mother, Genovefa Rosenberger was from the protestant city of Tübingen. She had become a Catholic when she married Johann on 28 December 1567. Mark, who would later become St. Fidelis, was the fifth of six children in the family. He was raised, as he would describe, “in the one, apostolic, Roman, and true faith” transmitted to him by his beloved parents. Educated in good manners, discipline and the fear of God he frequently approached the Sacraments, visited the sick and the poor, and spent many hours on his knees in Adoration.

For higher studies, Mark went to Freiburg im Breisgau in Baden-Württemberg (Germany). In this Jesuit college he advanced in classical studies, receiving a degree in philosophy in 1601. Subsequently he taught philosophy at this university while following courses in jurisprudence. During his time as a student, he was known for his modesty, meekness, and chastity. He was always generous to the poor, sometimes giving them the very clothes off his back.

In 1604 he accompanied, as preceptor (teacher-mentor), three young Swabian gentlemen on their travels through the principal parts of Europe. They were to visit the Low Countries under Spanish dominion as well as France and Italy to broaden the horizons of their human experiences. He lived this journey as a true and proper pilgrimage, exemplifying and encouraging a more spiritual way of life among his friends. Later he returned to the university and earned his Doctorate of Law around 1611.

For a time, he followed the legal profession. While nominated an assessor in the supreme court he opened a legal office and came to be known as the ‘poor man’s lawyer’. Adhered to the requirements of absolute honesty, he scrupulously refrained from all invectives, detractions, and whatever else might affect the reputation of any adversary. After a series of negative experiences and the unscrupulous attitude of his colleagues he found it was difficult to be both a good lawyer and a good Christian.

Leaving his legal practice behind, St. Fidelis decided to give his life directly to the service of Christ and the Church. After reading Jesuit Girolamo Piatti’s works on the consecrated life, St. Fidelis decided to join his brother George who had become a Capuchin in 1604, going by the name Br. Apollonius.

Around June 1612 he asked the Minister of the Swiss Capuchin Province, Alexander von Altdorf, to be admitted to the Order. The superior had him wait and suggested he be ordained priest first. In short order he received ordination and was accepted by Br. Angelo Visconti da Milano into the novitiate in Freiburg im Breisgau in October 1612, receiving the name Fidelis (faithful in Latin).

During the year of probation, there was no shortage of temptations to return to the world. In that period, he wrote a collection of prayers and meditations for personal use, (Exercitia spiritualia seraphicae devotionis) which revealed the affective and contemplative tone of his spirituality. After a year of religious formation at Freiburg, before taking vows on the 4th of October 1613, he wrote his will in which he provided scholarships for poor young Catholics of the Rey family and other relatives. Then he began four years of theology in Konstanz under the guidance of a friar of Polish origins, Br. Johann Baptist Fromberger. As soon he concluded these studies at Frauenfeld in 1618 he was immediately employed in preaching and in hearing confessions.

Through prayer, fasting, hair shirts, iron-pointed girdles, and disciplines St. Fidelis became known for his piety, while by caring for his neighbors he dutifully fulfilled the commandment of love. In 1621 when during a severe epidemic in town of Feldkirch, he cared for and cured many sick, and was especially revered for his work among Austrian soldiers, taking care of their bodies and souls. Many residents of the town and neighboring places were reformed by his zealous labors, and numerous Calvinists were converted. Soon he gained a reputation as an indefatigable preacher.

To counteract the spread of Calvinist Protestantism, a Swiss Catholic bishop sought help from the Capuchins. Having become well known for his fervor and holiness, St. Fidelis and eight other Capuchin friars were appointed by the Congregation for the Propagation of the Faith in Rome to preach, teach, and write in the canton of Grisons in Switzerland, with the goal of exhorting the people to return to the embrace of the Mother Church which had given them birth. Full of zeal they went from town to town, from village to village preaching in the pulpits of Catholic churches, in public places, and even in the meeting-places of the Calvinists themselves. Some Swiss Protestants responded with hostility, but many others, among them some prominent Calvinists like Rudolf von Gugelberg or Ralph de Salis were brought back to the Church. This made St. Fidelis an official enemy of the Calvinists who controlled much of that land. Being incensed at his success in converting their brethren, they loudly threatened St. Fidelis’ life, but he was ready to brave every peril to rescue souls from the errors of Calvin.

On 24 April 1622 under the protection of some Austrian imperial soldiers, St. Fidelis preached in the Church of the village of Seewis where, with great energy, he exhorted the Catholics to constancy in the faith. After Calvinists began an attack on the church, one of whom discharged a musket at St. Fidelis, he was persuaded by the Catholics to immediately flee with the Austrian troops. After leaving Seewis, the Austrian soldiers withdrew, but St Fidelis pressed on to preach at the village of Grüsch. On his way he was confronted by 20 Calvinist soldiers led by a minister. The Calvinists knew exactly who stood before them, called him a false prophet, and urged him to embrace their sect. He answered: “I am sent to you to confute, not to embrace your heresy. The Catholic religion is the faith of all ages, I do not fear death.” His skull was then cracked open with the butt of a sword. Then St.Fidelis rose again on his knees, and stretching forth his arms in the form of a cross, said with a feeble voice “Pardon my enemies, O Lord: blinded by passion they know not what they do. Lord Jesus, have mercy on me. Mary, Mother of God, succor me!” Another sword stroke cloved his skull and the saint collapsed. Still furious, the Calvinists proceeded to viciously stab the dying saint, and his left leg was hacked off in retribution for the numerous journeys he had made into Calvinist territory.

His body was quickly found and local Catholics buried him the next day. Six months later, the martyr’s body was exhumed and found incorrupt, but his head and left arm were separated from his body. The body parts were then placed into two reliquaries, one sent to the Cathedral of Coire at the behest of the bishop and laid under the High Altar; the other was placed in the Capuchin church at Weltkirchen, in Feldkirch, Austria. The rebels were soon after defeated by the imperial troops. The Protestant minister who had participated in Fidelis’ martyrdom was converted by this circumstance, made a public abjuration of Calvinism, and was received into the Catholic Church.

A few days before he affirmed his faith with his blood, in his last speech, St. Fidelis spoke of the Catholic faith in these words:

“Catholic faith, how stable, how firm you are, how well‐rooted, how well‐founded on a strong rock. Heaven and earth will pass away, but you can never perish. From the beginning the whole world has spoken against you, but you have triumphed mightily overall.

For this is the Victory which overcomes the world, our faith; this is what has brought the most powerful kings under Christ’s rule, and made peoples the servants of Christ.

What was it that made the holy apostles and martyrs undergo fierce struggles and terrible agonies, if not faith and above all faith in the resurrection?

What is it that has made hermits spurn pleasure, honors and wealth, and live a celibate life in solitude, if not living faith?

What is it that in these days causes true Christians to turn aside from what is easy and pleasant and undergo hardship and labor?

Living faith working through love – this is what leads men to put aside the goods of the present in the hope of those of the future, and to look to the future, rather than to the present.”

Canonized in 1746, St. Fidelis is the youngest Capuchin saint. He died at the age of forty-five, only ten years after entering religious life. Over three hundred miracles were attributed to his intercession during his canonization process.

References and Excerpts:

[1] CNA, “St. Fidelis of Sigmaringen,” Catholic News Agency. https://www.catholicnewsagency.com/saint/st-fidelis-of-sigmaringen-448 (accessed Apr. 15, 2023).

[2] “Saint Fidelis of Sigmaringen, Martyr.” https://sanctoral.com/en/saints/saint_fidelis_of_sigmaringen.html (accessed Apr. 15, 2023).

[3] “Memorial of Saint Fidelis of Sigmaringen, Priest and Martyr,” My Catholic Life! https://mycatholic.life/saints/saints-of-the-liturgical-year/april-24-saint-fidelis-of-sigmaringen-priest-and-martyr/ (accessed Apr. 15, 2023).

[4] “Saint Fidelis von Sigmaringen, Capuchin martyr,” CapDox. https://www.capdox.capuchin.org.au/saints-blesseds/saint-fidelis-von-sigmaringen/ (accessed Apr. 15, 2023).

[5] “Fidelis of Sigmaringen,” Wikipedia. Jan. 19, 2023. Accessed: Apr. 15, 2023. [Online]. Available: https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Fidelis_of_Sigmaringen&oldid=1134618057

Saint Simplicius

Saint Simplicius