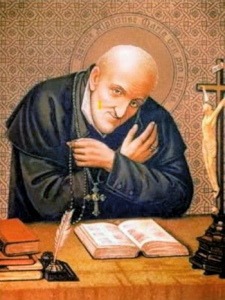

Saint Alphonsus Rodriguez

Saint Alphonsus Rodriguez

Confessor, Jesuit Coadjutor (1531-1617)

Feast – October 30

The Lombards were a Germanic people who conquered and ruled most of the Italian Peninsula starting in 568, establishing a Lombard Kingdom in north and central Italy. In 751, Aistulf, king of the Lombards, conquered what remained of the exarchate of Ravenna, the last vestige of the Roman Empire in northern Italy. He demanded the submission of Rome and a tribute of one gold solidus (about 4.5 grams of highly pure gold coin) per capita.

Pope Stephen II and a Roman envoy tried through negotiations to convince Aistulf to back down. When this failed, the Pope sent envoys to Pepin the Short, Mayor of the Palace of Neustria, (the western part of the Kingdom of the Franks) whom, on the 28th of July, 754, he anointed in the Basilica of Saint-Denis as king of the Franks and patrician of the Romans. In the spring of 755, Pepin summoned the army and sent envoys ahead to offer Aistulf an indemnity if he restored the Roman territories he had taken. The Frankish army crossed the Mont Cénis and defeated the Lombard army near Susa. Defeated, Aistulf submitted to some form of Frankish overlordship and promised under oath to return Ravenna and the other cities he had occupied to the Pope. The peace treaty was signed by the “Romans, Franks and Lombards” As soon as the Frankish army left Italy, he disregarded the treaty. On the 1st of January 756, Aistulf besieged Rome. The Pope appealed again to the Franks. After three months, Aistulf abandoned the siege. In April, a Frankish army once again invaded Italy and defeated the Lombards. Aistulf was forced to give hostages and pay annual tribute to the Franks. He also had to promise in writing to return the occupied territories to the Pope. The territories specified in the treaty of 756 had belonged to the Roman Empire. Envoys of the Empire met Pepin in Pavia and offered him a large sum of money to restore the lands to the Empire, but he refused, saying that they belonged to St Peter and the Roman church. The official Donation of Pepin followed extending the temporal rule of the popes beyond the duchy of Rome and provided a legal basis for the creation of the Papal States.

The creation of the Papal State, its security and security of its people forced Popes to get involved in international affairs, taking sides and positions in conflicts and wars, creating coalitions to maintain balance in Catholic Europe. Few kings and local rulers were saints, so times without military conflict were rare and even during times of peace the jealousy, greed and struggle for power continued.

In 1489, Pope Innocent VIII, in conflict with King Ferdinand I of Naples, excommunicated and deposed Ferdinand and offered the Kingdom of Naples to Charles VIII of France, grandson Marie of Anjou of the Angevin dynasty of Naples. Pope Innocent later settled his quarrel with Ferdinand and revoked the bans before dying in 1492, but this didn’t dissuade the French from invading. In July 1494, 30,000 men under Louis d’Orleans followed by another 25,000 troops under King Charles VIII entered the territories of the Duchy of Milan, advancing into the long Italian peninsula towards Naples. As a response to the speed of the greedy and brutal French advance, Pope Alexander VI formed an alliance of opponents of French hegemony in Italy. These included the Papal States, Republic of Venice, Kingdom of Naples, Kingdoms of Spain, Duchy of Milan, Holy Roman Empire, Republic of Florence known as the Holy League of 1495, or as the League of Venice which forced the French out of Italy in 1496.

In October 1511 Pope Julius II (the Warrior Pope) formed another Holy League against France.

In 1512 Ferdinand II of Aragon, the Regent of the Crown of Castile (the Iberian Peninsula), initiated a series of military campaigns to seize the Iberian part of the Kingdom of Navarre and move the Spanish border into the Pyrenees, which were easier to defend against French aggression.

On the 20th of May, 1521, a French-Navarrese expedition force stormed the fortress of Pamplona. At the Battle a cannonball ricocheting off a nearby wall crushed the leg of knight Inigo Lopez de Loyola. After the battle the Navarrese so admired his bravery that they carried him all the way back to his father’s castle in Loyola. He underwent several surgical operations to repair the leg, where his bones were rebroken and set.

His meditations during his long recovery set him on the road of conversion, from a regular knight to a Knight of Christ, today known as St. Ignatius of Loyola. In 1540 with St. Peter Faber and St. Francis Xavier, he founded the Society of Jesus (the Jesuits).

The purpose of the Society of Jesus, says the Summary of the Constitutions, is “not only to apply oneself to one’s own salvation and to perfection with the help of divine grace, but to employ all one’s strength for the salvation and perfection of one’s neighbor.”

Jesuit missions have generally included medical clinics, schools, and agricultural development projects as ways to serve the poor or needy while preaching the Gospel. Their educational institutions often adopt mottoes and mission statements that include the idea of making students “men and women for others.”

In addition to the vows of chastity, obedience, and poverty of other religious orders in the church, St. Ignatius instituted a fourth vow for Jesuits of obedience to the Pope, to engage in projects ordained by the pontiff.

In 1541 after attending the Diet of Ratisbon, St. Peter Faber was called by his superior “Father General” St. Ignatius Loyola to Spain. He visited Barcelona, Zaragoza, Medinaceli, Madrid, and Toledo.

When St. Peter Faber had given a mission in the city Segovia northwest of Madrid, in central Spain to preach, the Rodríguez family, a successful wool and cloth merchant family, provided him with hospitality. While staying with them he prepared the third of eleven children, then ten years old St. Alphonsus Rodriguez for his First Communion. This brought great joy to the entire family and especially to St. Alphonsus, who enjoyed serving the Jesuits when they lodged in his father’s country home. A few years later, he and his older brother were sent to the recently founded Jesuit college at Alcalá, but their studies unexpectedly ended when his father died two years later. His brother, after family affairs were settled, returned to school, but Alphonsus was obliged to remain at home to help his mother run the family business, which eventually he took over. In 1557 he married Maria Suárez with whom he had three children, a daughter and two sons. Five years later he was already a widower, with only one little boy of three years remaining for him to raise. A year later his mother died. From then on, he offered himself entirely to God and began a life of prayer and mortification. In his distress on the death of his third child, he turned to the Jesuits and offered himself as a candidate for priesthood, but his advanced age of 35, poor health and limited education made him unsuitable in the eyes of the Jesuits who interviewed him for entrance.

In 1568 St. Alphonsus left Segovia and went to Valencia where his spiritual father had been transferred and spent two years seeking the education necessary to become a priest employed as a preceptor of the young by two families of that city. When he renewed his request for admission willing to become a Jesuit brother if priesthood was out of the question the fathers who examined him came to the same negative conclusion as before. The provincial, however, recognized his holiness and said that if Alphonsus was not qualified to become a brother or a priest, he can enter to become a saint. He was admitted into the Society of Jesus as a lay brother on 31 January 1571, at the age of 40. After six months, in the midst of novitiate he was sent to college of Montesion in Palma on the island of Majorca where he remained in the humble position of porter for 46 years. His duties as doorkeeper were to receive visitors who came to the college; search out the teachers or students who were wanted in the parlor; deliver messages; and run errands. Each time the bell rang, St. Alphonsus envisioned that it is Our Lord standing outside seeking admittance. Always cheerful he distributed alms to the needy, consoled and gave advice to the troubled, and greeted students with encouragement. Numerous people came to hear the porter’s advice and this trend grew. For many he became a spiritual father, among them was the patron of missionary work among black slaves, St. Peter Claver.

He had a deep devotion to the Blessed Virgin Mary, especially as the Immaculate Conception, and would produce copies of the complete text of the Little Office of the Blessed Virgin Mary for the private recitation of people who asked.

The Jesuit doorkeeper was always appreciated for his kindness and holiness, but only after his death did his memoirs and spiritual notes reveal the quality and depth of his prayer life. The humble brother had been favored by God with remarkable mystical graces, ecstasies and visions of our Lord, our Lady and the saints. Maxims of his life was “In the difficulties which are placed before me, why should I not act like a donkey? When one speaks ill of him — the donkey says nothing. When he is mistreated — he says nothing. When he is forgotten — he says nothing. When no food is given him — he says nothing. When he is made to advance — he says nothing. When he is despised — he says nothing. When he is overburdened — he says nothing… The true servant of God must do likewise and say with David: Before You I have become like a beast of burden.”

For twenty years he had contented himself with a few hours of sleep on a table or in a chair until in 1591 he received an order to sleep a bed. The bodily mortifications which he imposed on himself were extreme. The demons would not leave alone this holy man. They tortured him mentally through frequent scruples and mental agitations as well as physical trauma. Twice he was thrown down a cement staircase by enemies of man’s salvation. He was afflicted with various illnesses, which plunged him into a sort of preliminary purgatory, but by casting himself into the abyss of the love of Jesus Crucified he did not change his life of modesty and service. He served a chapel where the elderly or infirm fathers celebrated late Masses. The extraordinary holiness shone out of the very ordinariness of his work as the Jesuit doorkeeper of a school.

His superiors, seeing the good work he was doing among the townspeople, were eager to have his influence spread far among his own religious community. So, on feast days they often let him into the pulpit of the refectory to have him give a lecture where entire community was sitting quietly past dinner to hear St. Alphonsus finish his preaching.

Out of obedience to his superiors in 1604 he began to write the story of his life.

He left a considerable number of manuscripts after him, they were not written with a view to publication, but put down by St. Alphonsus himself, or dictated to others.

St. Alphonsus died in 1617, already known and loved as a Saint by the population. In 1825 he was beatified and then canonized on the same day, the 15th of January, 1888, with his spiritual son St. Peter Claver, by Pope Leo XIII.

The Jesuits were instrumental in leading the Counter-Reformation, a comprehensive effort composed of apologetic and polemical documents and ecclesiastical configuration as decreed by the Council of Trent. By the mid-18th century, a flourishing Society had acquired a reputation in Europe for political maneuvering and economic success. Eager for more power, monarchs in many European states and their associates running shady businesses using slave labor in the colonies were unable to compete against areas run by the Jesuits, where bosses always cared more for workers material and spiritual wellbeing that their own, treating everybody the way St. Alphonsus did with love and kindness. The Jesuits were accused of being supranational, too autonomous, and too strongly allied to the papacy. Instead of adjusting the ways the colonies were run, political leaders pressured the papacy which reluctantly acceded to the anti-Jesuit demands of various Catholic kingdoms while providing minimal theological justification for the suppressions. The Portuguese Empire expelled Jesuits from their states in 1759, France in 1764, the Two Sicilies, Malta, Parma, the Spanish Empire in 1767, and the Society’s accumulated wealth and possessions were confiscated.

With his Papal brief, Dominus ac Redemptor on the 21st of July, 1773, Pope Clement XIV suppressed the Society, however, the order did not disappear. It continued underground operations in China, in Poland controlled by Russia and Prussia during the Partition era, and the United States. In 1814, a subsequent Pope, Pius VII, acted to restore the Society of Jesus to its previous provinces, and the Jesuits began to resume their work in those countries.

References and Excerpts:

[1] T. Modica, “Saint Alphonsus Rodriguez, pray for us – Good News Ministries,” Go!GoodNews Network, Oct. 30, 2019. https://gogoodnews.net/posts/saint-alphonsus-rodriguez/ (accessed Oct. 15, 2022).

[2] “Saint Alphonsus Rodriguez, Confessor, Jesuit Coadjutor.” https://sanctoral.com/en/saints/saint_alphonsus_rodriguez.html (accessed Oct. 15, 2022).

[3] “Saint Alphonsus Rodriguez | The Society of Jesus.” https://www.jesuits.global/saint-blessed/saint-alphonsus-rodriguez/ (accessed Oct. 15, 2022).

[4] “Alphonsus Rodriguez,” Wikipedia. Sep. 07, 2022. Accessed: Oct. 15, 2022. [Online]. Available: https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Alphonsus_Rodriguez&oldid=1109067328

[5] “Jesuits,” Wikipedia. Oct. 14, 2022. Accessed: Oct. 15, 2022. [Online]. Available: https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Jesuits&oldid=1115974369

Did you know?

Did you know?