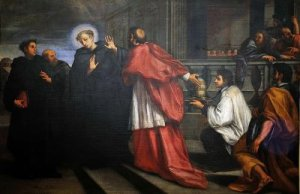

Saint Philip Benizi

Saint Philip Benizi

Servite Priest (1233-1285)

Feast- August 23

Henry IV was born in 1050, the son of Holy Roman Emperor Henry III and grandson of St. Henry II of the Salian dynasty. By the will of his father, at the age of two the boy became Duke of Bavaria, then in 1054 King of Germany, and subsequently in 1056 King of Italy and Burgundy. After his father’s death on the 5th of October, 1056, Henry was placed under his mother’s, Agnes of Poitou, guardianship. Unlike her late husband, she could not control the election of popes. This created an opportunity to restore the liberty of the Church during her rule. In 1062, in a conspiracy to remove Agnes from the throne, young Henry IV was abducted by a group of men, including Archbishop Anno II of Cologne (chaplain to Henry’s father) and Otto of Nordheim (Duke of Bavaria). Archbishop Anno II administered Germany until Henry came of age in 1065. As king, Henry, in his attempt to recover the royal estates that had been lost during his minority and expand his power surrounded himself with low-ranking but loyal officials to carry out his new policies. He insisted on his royal prerogative to appoint individuals to the highest church offices, which enabled him to demand benefices from the wealthy, bishops, and abbots. When Henry appointed a Milanese nobleman, Gotofredo, to the Archbishopric of Milan in 1070, Pope Alexander II excommunicated the new archbishop. In 1070 the local clerics appealed to the Holy See to prevent the installation of Henry’s candidate, Charles of Magdeburg, to the episcopal see of Constance. Henry denied Charles had bribed him, but he publicly admitted that his advisors may have received money from Charles. Pope Alexander II decided to investigate and summoned all German bishops who had been accused of simony or corruption to Rome, but he died in two months. On the death of Alexander II on 21 April 1073, as the obsequies were being performed in the Lateran Basilica, there arose a loud outcry from the clergy and people: “Blessed Peter has chosen Hildebrand the Archdeacon! Let Hildebrand be pope!”

In 1049 Pope Leo IX had named Hildebrand as deacon and papal administrator. Ten years later under Pope Nicholas II he was made archdeacon of the Roman church and become the most important figure in the papal administration. Out of admiration for Pope St. Gregory the Great, upon being elected by acclamation Hildebrand chose the name Gregory VII. As the new Pope he was well aware, and up to date with the challenges facing the Catholic Church. At the time the strength of the German monarchy had been seriously weakened; King Henry IV had to contend with great internal difficulties. This state of affairs was of material assistance to the Pope’s effort to restore the moral integrity and independence of the clergy and eradicate corruption in the Church. In a series of reforms initiated by St. Pope Gregory VII and the circle he formed in the papal curia, a ban on lay investiture was a key element. To liberate the Church from secular rulers it declared that the Pope alone could appoint or depose bishops and abbots or move them from one see to another. Reforms were finally confirmed by council held in the Lateran Palace on 28 February 1075.

In the meantime, Henry was forced by the Saxon Rebellion to come to amicable terms with the Pope at any cost. Consequently, in May 1074 he did penance at Nuremberg—in the presence of the papal legates—to atone for his continued friendship with excommunicated members of his council. He pledged obedience to the Pope and promised his support in the work of reforming the Church. This attitude was abandoned as soon as he defeated the Saxons at the First Battle of Langensalza on the 9th of June, 1075. Henry then tried to reassert his rights as the sovereign of northern Italy without delay. He nominated the cleric Tedald to the archbishopric of Milan. On December 8, 1075, Pope Gregory VII replied with a letter in which he accused Henry of breaching his word with his continued support of excommunicated councilors. At the same time the Pope suggested that the enormous crimes which would be laid to his account rendered him liable, not only to being barred from the Church, but to the deprivation of his crown.

Infuriated, Henry and his court convened national council in Worms, Germany, which met on the 24th of January 1076. The higher ranks of the German clergy and a Roman cardinal, Hugo Candidus, voted against Pope Gregory VII, calling him unfit for the Papacy. Henry IV wrote a letter to Gregory and told him that he was fired. Pope wrote back and declared the excommunication of Henry IV and informed all of his subjects that they no longer owed him any loyalty and could elect someone else as their new ruler.

Many German aristocrats called for the Pope to hold an assembly in Germany to hear Henry’s case. To prevent the Pope from sitting in judgement on him, Henry went to Italy as far as Canossa to meet with him in January 1077. His penitential “Walk to Canossa” was a success and Gregory VII had no choice but to absolve him. After squashing rivals and consolidating his position, Henry continued to appoint high-ranking clerics, for which the Pope again excommunicated him on 7 March 1080. In response the German and northern Italian bishops loyal to Henry elected the antipope, Clement III.

This started a war between the papacy and its supporters, the “church party” named the Guelphs, and the emperor with his “imperial party” known as the Ghibellines. The conflict officially ended when Pope Callixtus II and Emperor Henry V agreed on the Concordat of Worms in 1122, but the division amongst the people lasted much longer. In 1279, one hundred fifty-seven years later St. Philip Beniz was sent to Forli, Italy. He was heckled by Ghibellines and then physically attacked while preaching. His non-violent way of turning the other cheek caused a conversion in St. Peregrine Laziosi, the only son of the Peregrine’s family, the key supporters of the anti-papal faction. This conversion finally ended the conflict.

St. Philip was born of the renowned Benizi and Frescobaldi families in Florence on the Feast of the Assumption, August 15, 1233—the same day upon which the Blessed Virgin appeared to the seven noblemen of Florence, Saints Bonfilius, Alexis Falconieri, John Bonagiunta, Benedict dell’Antella, Bartholomew Amidei, Gerard Sostegni, and Ricoverus Uguccione, the founders of the Servite Order (Ordo Fratrum Servorum Sanctae Mariae /Order of Friar Servants of St. Mary).

From his very cradle St. Philip gave signs of his future sanctity. When he was scarcely five months old, he received the power of speech by a miracle. On beholding St. Alexis and St. Buonagiunta, two of the Seven Holy Founders, approaching in quest of alms, he exclaimed: “Mother, here come our Lady’s Servants; give them alms for the love of God.”

Amid all the temptations of his youth, he longed to become a Servant of Mary, but obedient to his father’s wish began to study medicine. A brilliant student, he studied at Paris, France, and Padua, Italy, receiving his doctorates in medicine and philosophy by age 19. The love of God was very strong in him, so that by self-discipline, praying, and particularly by reciting each day the office of the Holy Virgin he fulfilled the divine law to perfection. He practiced medicine for about a year, bringing help to the poor of Christ. In 1254 following a vision of the Virgin Mary, his doubts were solved. He quit everything and saying nothing of his studies and state he joined the Servites at Monte Scenario as a lay brother. In this humble state he led an austere and penitential life, sweetened by meditation on the sufferings of Our Lord. He couldn’t hide his great talents, wisdom, and knowledge, persuaded by superiors to use his gifts and background to further the Servite mission. He was ordained priest at Siena, Italy in 1258. Four years later in 1262 he become novice master at Siena and then superior of several Servite friaries. On the 5th of June 1267, in the Order’s General Chapter of Florence, St. Philip much against his protests was elected prior general of the order, an office he held for eighteen years, almost to the time of his death.

He watched over the Order of Our Lady with great care, in both its doctrine and its holiness. Like a father he would visit all the communities making long and arduous journeys. Once when ravaged by war and a subsequent famine in the province of Arezzo, the local friars, at the prayers of St. Philip to the Virgin Mary, by a miracle were provided with food. Under his leadership the number of communities and provinces in the Order increased significantly. As a follower of the Apostles, he was tireless in proclaiming the word of God. He sent some of his brethren to preach the Gospel in Scythia while he himself journeyed from city to city, travelling to Italy, the Netherlands and Germany, repressing civil dissensions and returning many to the obedience of the Roman Pontiff. His unremitting zeal for the salvation of souls won many, including the most unrepentant sinners. He was often seen rapt in ecstasy. Some of the saint’s miracles became well known. One day he met a half-naked leper, when this poor leper begged alms of him at Camigliano, a village of Siena, St. Philip having no money gave him his tunic. When the leper put it on, he was instantly cured.

The fame of this miracle spread far and wide and many of the Cardinals who were assembled at Viterbo for the election of a successor to Pope Clement IV considered him a candidate for the papacy.

When he heard the rumor, he went into hiding on Mount Tuniato until Pope St. Gregory X was chosen.

In the wake of the Second Council of Lyons of 1274 which put restrictions on mendicant orders he codified the Servite rules and applied his great gifts of wisdom in the Roman Curia along with Blessed Lotharingus and succeeded in preparing the way for definitive approval of the Order in the Church. For this reason, St. Philip is often called a holy Father of the Order.

He worked with Blessed Andrew Dotti, helped Saint Juliana of Cornillon found the Servite third order, and dispatched the first Servite missionaries to the East in 1284.

St. Philip lived his last few months in retirement in a Servite house in Todi, Italy.

Free from every stain of mortal sin, he was never weary of beseeching God’s mercy. From the time he was ten years old he daily prayed the Penitential Psalms. On his deathbed he recited verses of the Miserere, his cheeks streaming with tears; during his agony he went through a terrible contest to overcome the fear of damnation. A few minutes before he died, all his doubts disappeared and were succeeded by a holy trust. He uttered the responses to the final prayers in a low but audible voice; and when at last the Mother of God appeared before him, he lifted up his arms with joy and breathed a gentle sigh, as if placing his soul in Her hands. He died on the Octave of the Assumption, 1285.

The blind and lame were healed at his tomb, and the dead were brought back to life. His name having become illustrious by these and many other miracles, Pope Clement X in 1671, enrolled him among the saints.

References and Excerpts:

[1] “Henry IV, Holy Roman Emperor,” Wikipedia. Jun. 08, 2022. Accessed: Aug. 05, 2022. [Online]. Available: https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Henry_IV,_Holy_Roman_Emperor&oldid=1092152379

[2] “Pope Gregory VII,” Wikipedia. Jul. 16, 2022. Accessed: Aug. 05, 2022. [Online]. Available: https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Pope_Gregory_VII&oldid=1098614260

[3] ossm1236, “About St. Philip Benizi, OSM,” secularservites, Aug. 30, 2018. https://secularservites.org/about-st-philip-benizi-osm (accessed Aug. 05, 2022).

[4] “Saint Philip Benizi, Servite Priest.” https://sanctoral.com/en/saints/saint_philip_benizi.html (accessed Aug. 05, 2022).

[5] “CatholicSaints.Info » Blog Archive » Saint Philip Benizi.” https://catholicsaints.info/saint-philip-benizi/ (accessed Aug. 05, 2022).

[6] “St. Philip Benizi.” https://www.salvemariaregina.info/SalveMariaRegina/SMR-169/Benizi.htm (accessed Aug. 05, 2022).