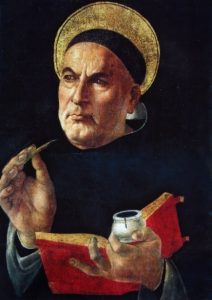

Saint Thomas Aquinas

Saint Thomas Aquinas

Doctor of the Church (1225-1274)

Feast-March 7

By the time of Muhammad’s death in June 632, most of the tribes of the Arabian Peninsula had converted to Islam and merged into a single Arab Muslim religious polity. Abu Bakr succeeded the leadership of the Muslim community as the first Rashidun Caliph, being elected at Saqifah. During his reign, he overcame several uprisings, collectively known as the Ridda wars. As a result, after two years of his reign he had consolidated and expanded dictatorial rule of the Islamic state over the entire Arabian Peninsula and commanded the initial incursions into the neighboring Sassanian and Byzantine empires. In the years following his death, this would eventually result in the Muslim conquests of Persia and the Levant. His successors continued conquering land for the Muslim empire. By 750 this empire stretched from Central Asia and South Asia, across the Middle East, all the way to North Africa, the Caucasus, and parts of Southwest Europe (Sicily and the Iberian Peninsula to the Pyrenees).

On 27 September 813 Abu al-Abbas Abdallah ibn Harun al-Rashid, better known by his regnal name Al-Ma’mun, became the seventh Abbasid caliph (The Abbasid Caliphate was the third caliphate to succeed the Islamic prophet Muhammad, founded by a dynasty descended from Muhammad’s uncle, Abbas ibn Abdul-Muttalib). Much of his domestic reign was consumed in pacification campaigns against rebellions and the rise of local strongmen. Well educated and with a considerable interest in scholarship he sawa need for intellectual growth among his people to meet the European standards of the times. Since the prosperity of the empire was based on annexing new territories, taking over land and properties, turning churches to the mosque and Christians to slave labor, the simple solution to the lack of education was the same. Al-Ma’mun ordered the Translation Movement, the flowering of learning and the sciences, The House of Wisdom in Baghdad, an institution where Greek works were translated into Arabic. He placed Hunayn ibn Ishaq in charge of the project, an Arab Nestorian Christian living in a community known for their high-literacy and multilingualism. The caliph also gave Hunayn the opportunity to travel to Byzantium in search of additional manuscripts of prominent authors. Many foreign works, among them the entire corpus of Aristotelian works, was translated into Arabic. Al-Kindi (801–873) the Muslim philosopher incorporated Aristotelian and Neoplatonist thought into an Islamic philosophical framework and Muslim intellectual world. This started the Islamic Golden Age, the age when Muslims benefited from others work, this time intellectually.

During the reign of Al-Hakam II (961 to 976) in the Caliph of Córdoba (southern Spain), a massive translation effort was undertaken at the western end of the Mediterranean Sea and many books were translated into Arabic.

Abu al-Walid Muhammad ibn Ahmad ibn Rushd, a twelve century chief judge and a court physician for the Almohad Caliphate, also known as Averroes, wrote some 38 commentaries on the works of Aristotle. Although his writings had an only marginal impact in Islamic countries, latin translations of Averroes’ work became widely available at the universities of 13th century Western Europe, being well received by scholasticists such as Boetius of Dacia, a leading philosopher at the Faculty of Arts in the University of Paris, and fellow profesor Siger of Brabant. This had a huge impact in the Latin West and lead to the rise of “Averroism” or “radical Aristotelianism” in universities which, with their materialistic approach, were undermining the teachings of the Catholic Church. We see a similar situation in the present day. God’s response was the Doctor Angelicus, St. Thomas Aquinas.

St. Thomas Aquinas was the youngest of nine children, son of Landulph, count of Aquino, and Theodora, Countess of Teano. He was born circa 1225 in Roccasecca, Italy, near Aquino, Terra di Lavoro, in the Kingdom of Sicily. Before St. Thomas was born, a holy hermit shared a prediction with his mother, foretelling that her son would enter the Order of Friars Preachers, become a great learner and achieve unequaled sanctity. His father was a knight in the service of Emperor Frederick II, so his brothers pursued military careers. At just 5 years old, following the tradition of the period, St Thomas was sent to the Abbey of Monte Cassino where his uncle was abbot to train among Benedictine monks. They described him as “a witty child” who “had received a good soul.” Diligent in study, he was thus early noted as being meditative and devoted to prayer, and his preceptor was surprised at hearing the child ask frequently: “What is God?” In his childhood he was the provider for the poor of the neighborhood during a famine; his father, meeting him in a corridor with the food he had succeeded in taking from the kitchen, asked him what he had under his cloak; he opened it and fresh roses fell on the ground. The nobleman embraced his son and amid his tears, gave him permission to follow thereafter all inspirations of his charity.

At the age of 14 he was enrolled at the studium generale (university) recently established in Naples. At the University he led a retired life of study and prayer, and continued his charities, giving all his superfluous possessions. There he studded arithmetic, geometry and astronomy under Petrus de Ibernia. He was recognized already by his professors as a genius. In Naples St. Thomas came under the influence of John of St. Julian, a Dominican preacher who was part of the active effort by the Dominican order to recruit devout followers. In 1243, he secretly joined an order of Dominican monks, receiving the habit in 1244.

This did not please his mother, Theodora, and rest of the family. In an attempt to prevent their interference, the Dominicans arranged to move St. Thomas to Rome, and then to Paris. However, while on his journey to Paris his brothers seized him as he was drinking from a spring and took him back to his parents at the castle of Monte San Giovanni Campano, where he was held prisoner for a year. Neither the caresses of his mother and sisters, nor the threats and stratagems of his brothers, could shake him in his vocation. He passed this time of trial tutoring his sisters leading one of them, Marotta, to renounce a brilliant marriage and instead embrace religious life, eventually becoming the abbess at the Monastery of Santa Maria in Capua.

Various family members became desperate to dissuade Thomas, who remained determined to join the Dominicans. His brothers endeavored to entrap him into sin, but the attempt only ended in the triumph of his purity. Two of his brothers resorted to the measure of hiring a prostitute to seduce him. As included in the official records for his canonization, Thomas drove her away wielding a burning log – with which he inscribed a cross onto the wall. He then fell into a mystical ecstasy, two angels appeared to him as he slept and said, “Behold, we gird thee by the command of God with the girdle of chastity, which henceforth will never be imperiled. What human strength cannot obtain, is now bestowed upon thee as a celestial gift.” The pain caused by the girdle was so sharp that Saint Thomas uttered a piercing cry, which brought his guards into the room. He never related this grace to anyone save Father Raynald, his confessor, and he wore the girdle till the end of his life. The girdle was given to the ancient monastery of Vercelli in Piedmont, and is now at Chieri, a town and commune in the Metropolitan City of Turin, Piedmont (Italy).

By 1244, seeing that all her attempts to dissuade St. Thomas had failed, Theodora sought to save the family’s dignity, arranging for him to escape at night through window. In her mind, a secret escape from detention was less damaging than an open surrender to the Dominicans.

After escaping, he went to Rome to meet Johannes von Wildeshausen, the Master General of the Dominican Order. In 1245 he was sent to study at the Faculty of the Arts at the University of Paris, where he most likely met Dominican scholar Bl. Albertus Magnus (Albert the Great), then the holder of the Chair of Theology at the College of St. James in Paris. In 1248 Bl. Albertus was sent by his superiors to teach at the new studium generale at Cologne. Bl. Albertus then appointed the reluctant St. Thomas as an apprentice professor. In Cologne he was instructing students on the books of the Old Testament and at the same time writing a literal commentary on Isaiah, on Jeremiah and on the Lamentations. St. Thomas was quiet and didn’t speak much, leading some of his fellow students to think that he was slow, but Bl. Albertus prophetically exclaimed: “You call him the dumb ox, but in his teaching he will one day produce such a bellowing that it will be heard throughout the world.”

In 1252 he returned to Paris to study for the master’s degree in theology and lectured on the Bible as a novice professor.

In 1256 St. Thomas was appointed regent master in theology at Paris. One of his first works upon assuming this office was Contra impugnantes Dei cultum et religionem (Against Those Who Assail the Worship of God and Religion), defending the mendicant orders (orders that adopted a lifestyle of poverty like the Dominicans, Franciscans, Augustinians, Carmelites, traveling, and living in urban areas for the purposes of preaching, evangelization, and ministry, especially to the poor) which had come under attack by William of Saint-Amour, a thirteenth-century academic, chiefly notable for his withering attacks on the friars. During his tenure from 1256 to 1259, St. Thomas wrote numerous works, including: Questiones disputatae de veritate (Disputed Questions on Truth) Expositio super librum Boethii De trinitate (Commentary on Boethius’s on the Trinity) – Boethius was a 6th-century Roman philosopher – and by the end of his regency, he was working on one of his most famous works, Liber de veritate catholicae fidei contra errores infidelium (Summa contra Gentiles). In 1259 St. Thomas completed his regency and left Paris. He returned to Naples where he was appointed as general preacher by the provincial chapter. In September 1261 he was called to Orvieto as conventual lector responsible for the pastoral formation of the friars unable to attend a studium generale.

In four years at Orvieto, St. Thomas was able to complete his Summa contra Gentiles, wrote the Catena aurea (The Golden Chain), the Contra errores graecorum (Against the Errors of the Greeks), and produced liturgy for the newly created feast of Corpus Christi and some of the hymns, such as the Pange lingua for Pope Urban IV.

In February 1265 the newly elected Pope Clement IV summoned St. Thomas to Rome to serve as papal theologian. The same year he was ordered by the Dominican Chapter of Agnani to teach at the studium conventuale at the Roman convent of Santa Sabina where he taught the full range of philosophical subjects, both moral and natural. While at the Santa Sabina he began work on the Summa theologiae, which he conceived specifically suited to beginning students.

St. Thomas remained at the studium at Santa Sabina from 1265 until he was called back to Paris in 1268 for a second teaching regency, a position he held until the spring of 1272. The reason for this sudden reassignment appears to have arisen from the rise of “Averroism” or “radical Aristotelianism” in the universities. A year before he re-assumed the regency at the 1266–67 Paris disputations, he argued that God is the source of both the light of natural reason and the light of faith. The first Franciscan master William of Baglione accused St. Thomas of encouraging Averroists. Deeply disturbed by the spread of Averroism and false accusations, he wrote On the Unity of Intellect, against the Averroists, (De unitate intellectus, contra Averroistas) in which he reprimands Averroism as incompatible with Christian doctrine, and On the Eternity of the World (De virtutibus and De aeternitate mundi) in which he dealt with controversial Averroist and Aristotelian beginning-lessness of the world. In effect Averroism came to be synonymous with atheism in late medieval usage. On the 10th of December 1270, the Bishop of Paris, Étienne Tempier, issued an edict condemning thirteen Aristotelian and Averroistic propositions as heretical and excommunicating anyone who continued to support them.

In 1272 the Dominicans from his home province called upon him to establish a studium generale wherever he liked and staff it as he pleased, so he took leave from the University of Paris and establish the institution in Naples and moved there as regent master. In his spare time he worked on the third part of the Summa, meanwhile giving lectures on various religious topics and preached to the people of Naples every day of Lent in 1273.

Looking to find a way to reunite the Roman Catholic Church and Eastern Orthodox Church which were divided by the Great Schism of 1054, Pope Gregory X convened the Second Council of Lyon to be held on the 1st of May, 1274, and summoned St. Thomas to attend. On his way to the council, riding on a donkey along the Appian Way, he struck his head on the branch of a fallen tree, after resting for a while, he set out again but after falling ill he stopped at the Cistercian Fossanova Abbey. The monks nursed him for several days, and as he received his last rites he died on 7 March 1274.

By a strange coincidence, three years to the very day after his death, some of his teachings were condemned as heresies. Stephen Tempier, Archbishop of Paris, influenced by Siger of Brabant and the Averrhoists, fostered by the adherents to the older Plato-Augustinian Scholasticism as well as by those who had personal motives of antagonism towards St. Thomas, issued a condemnation of 219 teachings of philosophy then current in Paris. Among these were some fundamental theses of St. Thomas. Archbishop Tempier denounced these as “manifest errors, or rather, as vain and false insanities” and the penalty of excommunication was imposed on anyone defending, teaching, or even listening to these teachings. Eleven days later, the Dominican Archbishop of Canterbury, Robert Kilwardby, caused the Masters of Oxford to condemn these and other Thomistic doctrines, not as heretical, but as dangerous. St. Thomas could not defend himself, but his teacher St. Albert could. He could be silent and bow to the decision of the authorities in Paris with a pretense of humility, but he did not. He made a long journey through the winter’s cold in order to present the cause of his beloved student. Some say that he was unsuccessful at Paris, but the weight of his words helped suppress any anti-Thomistic movement within the Order of Preachers. If it were not for this defense, Thomism as we know it today might well have perished.

The Church has venerated his numerous writings as a treasure of sacred doctrine; in naming him the Angelic Doctor she has indicated that his science is more divine than human and regards him as the model teacher for those studying for the priesthood, combining gifts of intellect with the most tender piety.

References and Excerpts:

[1] “Saint Thomas Aquinas, Doctor of the Church.” https://sanctoral.com/en/saints/saint_thomas_aquinas.html (accessed Mar. 07, 2022).

[2] “Thomas Aquinas,” Wikipedia. Feb. 23, 2022. Accessed: Mar. 07, 2022. [Online]. Available: https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Thomas_Aquinas&oldid=1073654883

[3] R. Comeau, “THE CONDEMNATION OF ST. THOMAS,” p. 5, [Online]. Available: https://www.dominicanajournal.org/wp-content/files/old-journal-archive/vol27/no2/dominicanav27n2condemnationstthomas.pdf