Saint James of The March of Ancona

Saint James of The March of Ancona

Franciscan Priest (1391-1476)

Feast – November 28

The Pharisee took up his position and spoke this prayer to himself, ‘O God, I thank you that I am not like the rest of humanity—greedy, dishonest, adulterous—or even like this tax collector. I fast twice a week, and I pay tithes on my whole income. (Luke 18:11-12)

Pietro da Fossombrone, known also as Angelo da Clareno was born about 1248, and entered the Franciscan order around 1270. Believing that the rule of St Francis was not being observed and interpreted according to the mind and spirit of the Seraphic Father, he retired to a hermitage with a few companions in the Marche of Ancona along the Adriatic Sea in central Italy and formed a new branch of the order known as the “Clareni.” This started poisonous disputes concerning poverty among Franciscans and gave birth to various heretical sects of the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries called Fraticelli. Fraticelli regarded the wealth of the Church as scandalous, and that of individual churchmen as invalidating their status.

In 1391 in the same region, Marche of Ancona, at Monteprandone was born into a poor family Dominic Gangala – St. James of The March of Ancona.

His parents raised him in the fear and love of God. He began his studies at Offida under the guidance of his uncle, a priest who later sent him to school in the nearby town of Ascoli Piceno. While still young he was sent to the University of Perugia, where he studied civil and canon law with such remarkable success that he received a doctor’s degree in both subjects. This qualified him to be chosen preceptor to the children of a young gentleman of Perugia. He went with him to Florence, to aid in the administration of a juridical office the nobleman had obtained there. When St. James was about to be engulfed in the whirlpool of worldly excesses and the vanity of the world, he felt a singular attraction for the religious life. At first, he thought of joining the contemplative Carthusians, but almighty God had a different plan for him.

While traveling one day near Assisi he went into the Church of the Portiuncula to pray. Moved by the fervor of the Franciscan friars and inspired by the example of their blessed founder, he determined to petition in that very place for the habit of the Order. He was received into the Order of Friars Minor on the 26th of July 1416 at the age of 25 in the chapel of the Portiuncula at the convent of Our Lady of the Angels and took the monastic name Jacobus, James in English.

During his novitiate his life became a constant spiritual war against the world, the flesh and the devil in silence of his cell, adding extraordinary fasts and vigils to his assiduous prayer he became a model of religious perfection. Having finished his novitiate at the hermitage of the Carceri, near Assisi, he studied theology under St. Bernardino of Siena at Fiesole, near Florence.

St. James led a most austere life; he slept on the bare floor three hours a night while the remainder of the night he spent meditating on the sufferings of Christ. He scourged himself daily and like St. Francis observed a 40-day fast 7 times a year. Bread and water were his regular food, sometimes he added beans or vegetables. This concerned St. Bernardino of Siena who instruct St. James to moderate his penances in order to conserve his strength.

While studying he became widely recognized for his oratory and soon after his ordination on June 13th, 1420, he was sent out with St. John Capistrano as a missionary.

St. James undertook this high calling with untiring zeal delivering forceful and effective sermons. First, He began to preach in Tuscany, in the Marches, and Umbria than all over Italy and through 13 Central and Eastern European countries: Dalmatia, Croatia, Albania, Bosnia, Austria, Bohemia, Saxony, Prussia, Poland, Denmark, Norway, Sweden, and Russia, laboring for the salvation of thousands of souls. St. James always traveled without any provisions other than his confidence in God. If he found no aid or was without lodging, he rejoiced in his union with Lady Poverty, to whom he was joined by his religious profession.

He carried out that ministry with such great fervor and power that he never failed to touch the most hardened hearts and produce truly miraculous conversions. Inspired by his apostolic example, more than 200 of the noblest young men of Germany were impelled to enter the Franciscan Order. The crowds who came to hear him were so great that the churches were not large enough to accommodate them, and it became imperative for him to preach in the public squares. For more than 50 years he traveled spreading devotion to the Holy Name of Jesus and preached penance. This extremely popular preacher was instrumental in converting 36 women of bad repute by a single sermon on St. Mary Magdalen at Milan. At Buda he effected the miraculous cessation of a furious sedition by simply showing the crucifix to the people; the rebels themselves took him upon their shoulders and carried him through the streets of the city. At Prague he brought back to God many who had fallen into error, and when a magician wanted to dispute with him, he rendered him mute and thus obliged him to retire in confusion. He raised from dangerous illness the Duke of Calabria and the King of Naples.

It is said that he brought 50,000 heretics into the bosom of the Church and led 200,000 unbelievers to baptism. God granted St James gifts of wisdom and prophesy, so popes and princes were seeking his counsel.

With St. John of Capistrano, Albert of Sarteano, and St. Bernardino of Siena, St. James is considered one of the “four pillars” of the Observant movement among the Franciscans, especially known for their preaching.

From 1427 onward, St. James combated heretics and was on legations in Germany, Austria, Sweden, Denmark, Bohemia, Poland, Hungary. In Bosnia he was also commissary of the Friars Minor. At the time of the Council of Basle he promoted the union of the moderate Hussites with the Church, and that of the Greeks in the Council of Ferrara-Florence.

After Constantinople fell on 29 May 1453 to the Ottomans, he joined Saint John of Capistrano to preach a crusade against the Turks terrorizing Western Europe and in 1456 he was sent to Hungary as his successor. St. James founded several monasteries in Bohemia, Hungary, and Austria.

In Italy he was appointed inquisitor against a heretic sect called the Fratelli. When he was offered the archiepiscopal dignity of the see of Milan in 1460, he declined with words: “I have no other desire upon earth than to do penance and to preach penance as a poor Franciscan.”

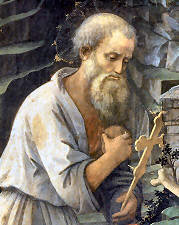

Especially devoted to the Precious Blood of Jesus, he, himself, was brought up on heresy charges during the Dominican Inquisition in 1462. The Pope intervened, ordering the case put on permanent hold, with no decision ever rendered on his statements. However, during the course of the inquisition, James was the victim of attempted assassinations twice, both times in the form of a poisoned chalice (as he is frequently depicted in art). Twice assassins lost their nerve when they came face to face with him.

The Saint’s love for the poor and disdain for extremely high interest rates led him to establish the montes pietatis—literally, mountains of charity— which were nonprofit credit organizations that lent money on pawned objects at very low rates and were made very popular by his protégé, St. Bernardine of Feltre.

St. James spent the last three years of his life in Naples. Worn out by his many labors as well as advanced age, he died on November 28, 1476, in the 85th year of his life, 60 years of which were consecrated to God in the religious state.

His body remained in a crystal coffin, incorrupt, flexible, and emitting a fragrant perfume in the Franciscan church of Santa Maria la Nova in Naples for over five centuries until 2001 when it was finally transferred to his birthplace of Monteprandone.

Beatified by Pope Urban VIII, 1624, he was canonized by Benedict XIII, 1726.

References and Excerpts:

[1] F. Media, “Saint James of the Marche | Franciscan Media.” https://www.franciscanmedia.org/saint-of-the-day/saint-james-of-the-marche (accessed Dec. 28, 2020).

[2] E. Staff, “Saint James of the Marches, Confessor – REGINA Magazine,” Nov. 28, 2016. https://www.reginamag.com/saint-james-of-the-marches/ (accessed Dec. 28, 2020).

[3] “Saint James of The March of Ancona, Franciscan Priest.” https://sanctoral.com/en/saints/saint_james_of_the_march_of_ancona.html (accessed Dec. 28, 2020).

[4] “Saint James of the March.” https://www.roman-catholic-saints.com/saint-james-of-the-march.html (accessed Dec. 28, 2020).

[5] “CATHOLIC ENCYCLOPEDIA: St. James of the Marches.” https://www.newadvent.org/cathen/08278b.htm (accessed Dec. 28, 2020).

[6] “28. St. James of the March, Priest – Divine Redeemer Sisters – American region.” http://www.divine-redeemer-sisters.org/saint-of-the-day/november/28-st-james-of-the-march-priest (accessed Dec. 28, 2020).

[7] “James of the Marches,” Wikipedia. Dec. 16, 2020, Accessed: Dec. 28, 2020. [Online]. Available: https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=James_of_the_Marches&oldid=994637339.

Saint Hilarion the Great

Saint Hilarion the Great