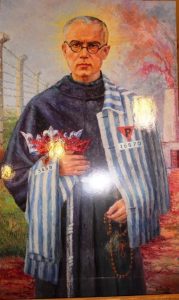

Saint Maximilian Kolbe

Saint Maximilian Kolbe

Martyr (1894-1941)

Feast- August 14

The Knight of the Immaculate Virgin was born on January 8th, 1894 in Zduńska Wola, located at the part of partitioned Kingdom of Poland under Russian occupation, the second son of weaver Julius Kolbe (German descent) and midwife Maria Dąbrowska, an exceptionally pious family, all of whose living members became religious, including, eventually his parents. He had four brothers. Shortly after his birth, his family moved to Pabianice. Maria Dabrowska, formed his early years in the daily recitation of the Angelus, the Holy Rosary, and the Litany to Our Lady. The practice of these pious Marian devotions, however, would not subdue young Raymond’s natural, mischievous nature. One day in 1906 his mother, no longer knowing what to do with him, said to him: “My child, what will become of you?” He went to pray before a statue of his heavenly Mother. Tearfully and humbly he asked Her the same question. He was transformed that day into a new person, by a vision; “That night I asked the Mother of God what was to become of me. Then she came to me holding two crowns, one white, the other red. She asked me if I was willing to accept either of these crowns. The white one meant that I should persevere in purity, and the red that I should become a martyr. I said that I would accept them both.”

At age thirteen, Raymond Kolbe became fascinated by the Franciscan ideals preached by two Conventual Franciscans who conducted a parish mission at his church in Pabianice.

Soon thereafter, in 1907, he and his elder brother, Francis, joined the Conventual Franciscans. They enrolled at the Conventual Franciscan minor seminary in Lwow. He fervently sought to draw profit from all the means accessible for his personal sanctification. Here he excelled in mathematics and physics and his teachers predicted a brilliant future for him in science. Others, seeing his passionate interest in all things military, saw in him a future strategist. For a time indeed, his interest in military affairs together with his fiery patriotism made him lose interest in the idea of becoming a priest. Tiny Raymond dreamed the political reunification of their Motherland would come about through the valorous efforts of some knights of Our Lady of Czestochowa. His courageous and generous soul to undertake great things for his country was intensified by his ardent devotion to the glorious Patroness of Poland.

As all their children were in seminaries, his parents separated to enter religious life. In 1910, Raymond was allowed to enter the novitiate, where he was given the religious name Maximilian. He professed his first vows in 1911. Sent to Rome in 1912, where he attended the Pontifical Gregorian University. Maximilian gradually discovered that in order to be a saint, one must be conformed to the likeness of Christ, a likeness which is authenticated in the perfection of the Immaculate.

In 1914, with final vows he adopted the additional name of Maria (Mary).

He earned a doctorate in philosophy in 1915. From 1915 he continued his studies at the Pontifical University of St. Bonaventure where he earned a doctorate in theology. He was ordained in 1918 on April 28th, the feast of the Marian apostle, Saint Louis Mary de Montfort.

The love of fighting didn’t leave him, but while he was in Rome he stopped seeing the struggle as a military one. He didn’t like what he saw of the world, in fact he saw it as downright evil.

During his time as a student, he witnessed vehement demonstrations against Popes St. Pius X and Benedict XV in Rome during an anniversary celebration by the Freemasons. According to Kolbe,

“They placed the black standard of the “Giordano Brunisti” under the windows of the Vatican. On this standard the archangel, St. Michael, was depicted lying under the feet of the triumphant Lucifer. At the same time, countless pamphlets were distributed to the people in which the Holy Father (i.e., the Pope) was attacked shamefully.”

The fight, he decided, was a spiritual one. The world was bigger than Poland and there were worse slaveries than earthly ones. The fight was still on, but he would not be waging it with the sword.

Soon afterward, Having obtained permission from his superiors at the Conventual Franciscan Collegio-Serafico in Rome on October 16, 1917, with six other friars, he founded the Militia Immaculatae (Army of the Immaculate One/Knights of the Immaculate), with the aim of “converting sinners, enemies of the Catholic Church, heretics and schismatics, particularly freemasons, through the intercession of the Virgin Mary. So serious was Kolbe about this goal that he added to the Miraculous Medal prayer:

O Mary, conceived without sin, pray for us who have recourse to thee. And for all those who do not have recourse to thee; especially the Masons and all those recommended to thee.

A militia in honor of the Virgin destined to crush the head of the ancient serpent, master of pride and revolt. There should be an army at Her disposition, he was certain, and then She Herself could do all through its well-disciplined ranks. He found willing collaborators — a small group at first — ready to consecrate themselves to Her forever, for the fulfillment of Her desires.

When St. Maximilian returned to Poland in 1919, he rejoiced to see his country free once again, a liberation which he attributed to Mary Immaculate. Pius XI, in response to a request from the Polish bishops, had just promulgated the Feast of Our Lady, Queen of Poland, and Fr Maximilian wrote: “She must be the Queen of Poland of every Polish heart. We must labor to win each and every heart for her.” He set himself to extend the influence of his Crusade and formed cells and circles all over Poland.

From 1919 to 1922 he taught at the Cracow seminary. However, because of his failing health and having contracted tuberculosis, he was deemed unsuitable for the task. His superiors, therefore, decided to assign him to the office of confessor. Far from helping his already weakened condition, he became increasingly frail, and was subsequently consigned to the sanitarium of Zakopane.

But his zeal for souls, characteristic of a true saint, did not diminish because of his physical ailments. He provided various spiritual services among his sick companions and instilled in them the love of Our Lady. After having recovered from a long confinement – which served as a period of silence and purification for him – he was prepared to launch a new apostolic endeavor.

In January 1922, invoking the special assistance of Saint Thérèse of Lisieux he began to publish a monthly review, the Knight of the Immaculate, similar to the French Le Messager du Coeur de Jesus (Messenger of the Heart of Jesus), in Krakow. Its aim was to “illuminate the truth and show the true way to happiness”. As funds were low, only 5,000 copies of the first issue were printed. It all started in the humble surroundings of the friary in Grodno where Father Maximilian established a printer. From now on the review began to grow. In 1927, 70,000 copies were being printed. The Grodno Friary became too small to house such a mammoth operation, so Fr Maximilian began to look for a site nearer to Warsaw. Prince Jan Drucko-Lubecki offered him some land at Teresin, west of Warsaw. St. Maximilian promptly erected a statue of Mary Immaculate there, and the monks began the arduous work of construction. On 21 November 1927, the Franciscans moved from Grodno to Teresin and on 8 December, the friary was consecrated and was given the name of Niepokalanow, the City of the Immaculate.

The prodigious growth of this enterprise left those who could not understand its heavenly Sources mystified and sometimes very much contradicted. At first, Niepokalanow consisted of no more than a few shacks with tar-paper roofs. Soon the walls were cracking, so to speak, by the arrival of printing presses and, above all, religious vocations. To cope with the flood of vocations all over Poland, a junior seminary was built at Niepokalanow “to prepare priests for the missions capable of every task in the name of the Immaculate and with Her help.” A few years later, there were more than a hundred seminarians and the numbers were still growing. The City of the Immaculate was organized, where some 50 low buildings were set up and mobilized for the various facets not only of publishing, but of the Franciscan life of prayer. Before long, Niepokalanow had become one of the largest (some say the largest) friaries in the world. In 1939, it housed 762 inhabitants: 13 priests, 18 novices, 527 brothers, 122 boys in the junior seminary and 82 candidates for the priesthood. No matter how many labourers were in the vineyard, there was always work for more. Among the inhabitants of Niepokalanow there were doctors, dentists, farmers, mechanics, tailors, builders, printers, gardeners, shoemakers and cooks. The place was entirely self-supporting. They lived heroic lives of poverty, continuous prayer and voluntary penance, united in their mission of evangelizing not only Poland, but the whole world! Day and night, the friars spent themselves in promoting Catholic doctrines, particularly those concerning Our Blessed Lady. They did all this in view of cultivating the need for conversion and sanctification of souls, both on the individual and collective levels, via the mediation of the Blessed Virgin Mary.

“Niepokalanow”, said Fr Maximilian, “is a place chosen by Mary Immaculate and is exclusively dedicated to spreading her cult. All that is and will be at Niepokalanow will belong to her. The monastic spirit will flourish here; we shall practice obedience and we shall be poor, in the spirit of St Francis.”

They continued printing the Knight of the Immaculate — which had now reached the incredible circulation figure of 750,000 per month — and to produce other publications as well. In 1935, they began to produce a daily Catholic newspaper, The Little Daily, of which 137,000 copies were printed on weekdays and 225,000 on Sundays and holydays and eventually reached a circulation of one million. Miscellaneous books, magazines, and pamphlets for people in all walks of life were freely circulated by the friars.

St. Maximilian, despite a health which was never other than precarious — for he was undermined by tuberculosis for long years, and virtually abandoned at one time as incurable – with the permission of his superiors, considering the need for further expansion, started a mission in Japan with four other friars in 1930. The going was hard. The Poles’ only shelter was a wretched hut whose walls and roof were caving in. They slept on what straw they could find, and their tables were planks of wood. But despite such hardships, and the fact that they knew not a word of the Japanese language, and had no money, on 24 April 1930, exactly a month after their arrival, a telegram was dispatched to Niepokalanow: “Today distributing Japanese Knight. Have printing press. Praise to Mary Immaculate.”

By 1931 he founded a monastery at the outskirts of Nagasaki (it later gained a novitiate and a seminary), they established a new “City of the Immaculate” (Mugenzai no Sono – literally “Garden of the Immaculate”), thereby introducing his ideal, the Immaculate, to the Orient. In spite of problems with local authorities, language, culture, and climate, “Seibo no Kishi,” the Japanese version of the magazine “Knight of the Immaculate” the first 10,000 copies had swollen to 65,000 by 1936. The monastery he founded remains prominent in the Roman Catholic Church in Japan. St. Maximilian Kolbe built the monastery on a mountainside that, according to Shinto beliefs, was not the side best suited to be in harmony with nature. Local people thought Fr Maximilian was crazy to be building on steep ground sloping away from the town; but in 1945, when the atomic bomb all but levelled Nagaskai, Mugenzai no Sono sustained no more damage than a few broken pains of stained glass. Today it forms the centre of a Franciscan province.

Although he often complained of the lack of manpower and machines needed to serve the people of Japan, in 1932 he was already seeking fresh pastures. On 31 May he left Japan and sailed to Malabar where, after a few initial difficulties, he founded the third Niepokalanow. Poor health forced Kolbe to return to Poland in 1936, his major superiors appointed him as the superior of the Polish City of the Immaculate whose apostolic potentials had peaked at that moment in time. Since no priests could be spared for Malabar, that idea had to be given up.

Two years later, in 1938, St. Maximilian started a radio station, the Radio Niepokalanów.

Upon his return to Poland, with somewhat of a prophetic “instinct,” knowing perhaps his end was approaching, he busied himself giving continuous and regular spiritual conferences to the friars explaining; “The more souls there will be, totally given to the guidance of the Immaculate, the more Saints there will be, and very great Saints. Sanctity is not a luxury, but a simple duty, since Our Lord said,’ Be perfect, as your Heavenly Father is perfect.’” He gave them as a formula, w=W — signifying the human will perfectly united and equivalent, through Her, to the Will of God. He said to them,” Our sanctification is Her affair and Her specialty, since we belong unconditionally to Her.”

Just before the Second World War broke out, St. Maximilian spoke to his friars about suffering. They must not be afraid, he said, for suffering accepted with love would bring them closer to Mary. All his life, he had dreamt of a martyr’s crown, and the time was nearly at hand.

After the outbreak of World War II, which started with the invasion of Poland by Germany, on September 19, 1939 Father Maximilian and many of the friars were arrested. Their incarceration lasted approximately two months. He refused to sign the Deutsche Volksliste, which would have given him rights similar to those of German citizens in exchange for recognizing his German ancestry. Upon his release from prison on December 8, 1939, the feast day of the Immaculate Conception of his Heavenly Queen, Father Maximilian returned to a ransacked Niepokalanów, galvanized into a new kind of activity. He began to organize a shelter for 3,000 Polish refugees, among whom were 2,000 Jews. “We must do everything in our power to help these unfortunate people who have been driven from their homes and deprived of even the most basic necessities. Our mission is among them in the days that lie ahead.” The friars shared everything they had with the refugees. They housed, fed and clothed them, and brought all their machinery into use in their service.

St. Maximilian Kolbe also received permission to continue publishing religious works, though significantly reduced in scope. The monastery thus continued to act as a publishing house, issuing a number of anti-Nazi German publications. “No one in the world can change Truth,” he wrote. “What we can do and should do is to seek truth and to serve it when we have found it. The real conflict is the inner conflict. Beyond armies of occupation and the hecatombs of extermination camps, there are two irreconcilable enemies in the depth of every soul: good and evil, sin and love. And what use are the victories on the battlefield if we ourselves are defeated in our innermost personal selves?”

On 17 February 1941, the monastery was shut down by the German authorities. That day Kolbe and four others were arrested by the German Gestapo and sent to the infamous Pawiak prison in Warsaw. Here he was singled out for special ill-treatment. A witness tells us that in March of that year an SS guard, seeing this man in his habit girdled with a rosary, asked if he believed in Christ. When the priest calmly replied, “I do”, the guard struck him. The SS man repeated his question several times and receiving always the same answer went on beating him mercilessly. Shortly afterwards the Franciscan habit was taken away and a prisoner’s garment was substituted. On 28 May, St. Maximilian was with over 300 others who were transferred to Auschwitz as prisoner 16670. Continuing to act as a priest he would translate his theological and spiritual insights into practical words and actions for his fellow inmates, by tangibly showing that there is God, and therefore, love and hope exist even in the midst of horrific genocide in the camps of Auschwitz where he was subjected to violent harassment. On the last day of May he was assigned with other priests to the Babice section which was under the direction of “Bloody” Krott, an ex-criminal. “These men are layabouts and parasites,” said the Commandant to Krott, “get them working.” Krott forced the priests to cut and carry huge tree trunks. The work went on all day without a stop and had to be done running — with the aid of vicious blows from the guards. Despite his one lung, St. Maximilain accepted the work and the blows with surprising calm. Krott conceived a relentless hatred against the Franciscan and gave him heavier tasks than the others. Sometimes his colleagues would try to come to his aid but he would not expose them to danger. Always he replied, “Mary gives me strength. All will be well.” At this time he wrote to his mother, “Do not worry about me or my health, for the good Lord is everywhere and holds every one of us in his great love.”

One day, Krott found some of the heaviest planks he could lay hold of and personally loaded them on the Franciscan’s back, ordering him to run. When he collapsed, Krott kicked him in the stomach and face and had his men give him fifty lashes. When the priest lost consciousness Krott threw him in the mud and left him for dead. But his companions managed to smuggle him to the camp hospital.

Although he was suffering greatly, he secretly heard confessions in the hospital and spoke to the other inmates of the love of God. He seemed never to think of himself. He was once asked whether such self-abnegation made sense in a place where every man was engaged in a struggle for survival, and he answered: “Every man has an aim in life. For most men it is to return home to their wives and families, or to their mothers. For my part, I give my life for the good of all men.”

The cruelest treatment could not alter his calm. He brought light to the despairing and renewed the faith of all with whom he came into contact.

Fr Zygmunt Rusczak remembers: “Each time I saw Fr Kolbe in the courtyard I felt within myself an extraordinary effusion of his goodness. Although he wore the same ragged clothes as the rest of us, with the same tin can hanging from his belt, one forgot his wretched exterior and was conscious only of the charm of his inspired countenance and of his radiant holiness.”

At the end of July 1941, ten prisoners disappeared from the camp, prompting SS-Hauptsturmführer Karl Fritzsch, the deputy camp commander, to pick 10 men to be starved to death in an underground bunker to deter further escape attempts. When one of the selected men, Franciszek Gajowniczek, cried out, “My wife! My children!” St. Maximilian Kolbe volunteered to take his place.

Bruno Borgowiec was an eyewitness of those last terrible days, for he was an assistant to the janitor and an interpreter in the underground Bunkers. He tells us what happened: “In the cell of the poor wretches there were daily loud prayers, the rosary and singing, in which prisoners from neighboring cells also joined. When no SS men were in the Block, I went to the Bunker to talk to the men and comfort them. Fervent prayers and songs to the Holy Mother resounded in all the corridors of the Bunker. I had the impression I was in a church. Fr Kolbe was leading, and the prisoners responded in unison. They were often so deep in prayer that they did not even hear that inspecting SS men had descended to the Bunker; and the voices fell silent only at the loud yelling of their visitors. Since they had grown very weak, prayers were now only whispered. At every inspection, when almost all the others were now lying on the floor, Fr Kolbe was seen kneeling or standing in the center as he looked cheerfully in the face of the SS men. Two weeks passed in this way. Meanwhile one after another they died, until only Fr Kolbe was left.” This the authorities felt was too long; the cell was needed for new victims. On August 14, 1941 after fourteen days, a guard, named Bock, the head of the sickquarters, found him alone, still alive, seated in a corner in total deprivation, still praying. He stretched out his fleshless arm to the jailers who had come to finish him off with a hypodermic syringe. His expression in death was described as ecstatic;” he was gazing upward, as if to welcome the One he saw coming for his soul. His face was calm and radiant.” His remains were cremated on 15 August, the feast day of the Assumption of Mary.

Jerzy Bielecki, a Polish Catholic who managed to escape successfully in 1944 from Auschwitz concentration camp, recipient of the Righteous Among the Nations award, declared that Fr Kolbe’s death was “a shock filled with hope, bringing new life and strength. …It was like a powerful shaft of light in the darkness of the camp.”

On 12 May 1955, Maximilian Maria Kolbe was recognized as a Servant of God, declared venerable by Pope Paul VI on January 30th, 1969, beatified as a Confessor of the Faith by the same Pope in 1971. In June, 1979, Pope John Paul II would visit St. Maximilian’s death chamber in Auschwitz, proclaiming him “Patron Saint of our Difficult Age.” Canonized as a saint by Pope John Paul II on 10 October 1982. Upon canonization, the Pope declared St. Maximilian Kolbe a martyr of charity.

After his canonization, St. Maximilian Kolbe’s feast day was added to the General Roman Calendar.

He is one of ten 20th-century martyrs who are depicted in statues above the Great West Door of Westminster Abbey, London. In 2000, the National Conference of Catholic Bishops (U.S.) designated Marytown, located in Libertyville, Illinois, home to a community of Conventual Franciscan friars, as the National Shrine of St. Maximilian Kolbe, featuring the Kolbe Holocaust Exhibit.

The Polish Senate declared the year 2011 to be the year of St. Maximilian Kolbe.

References and Excerpts

[1] “Saint Maximilian Kolbe, Martyr.” [Online]. Available: http://sanctoral.com/en/saints/saint_maximilian_kolbe.html. [Accessed: 17-Aug-2018].

[2] “Biography,” St. Maximilian Kolbe. .

[3] “Saint Maximilian Kolbe | Catholic-Pages.com.” [Online]. Available: http://www.catholic-pages.com/saints/st_maximilian.asp. [Accessed: 17-Aug-2018].

[4] “Maximilian Kolbe,” Wikipedia. 15-Aug-2018.